In honor of Father’s Day, this June edition of the Puggle features the latest news and research about the importance of fathers in girls’ education.

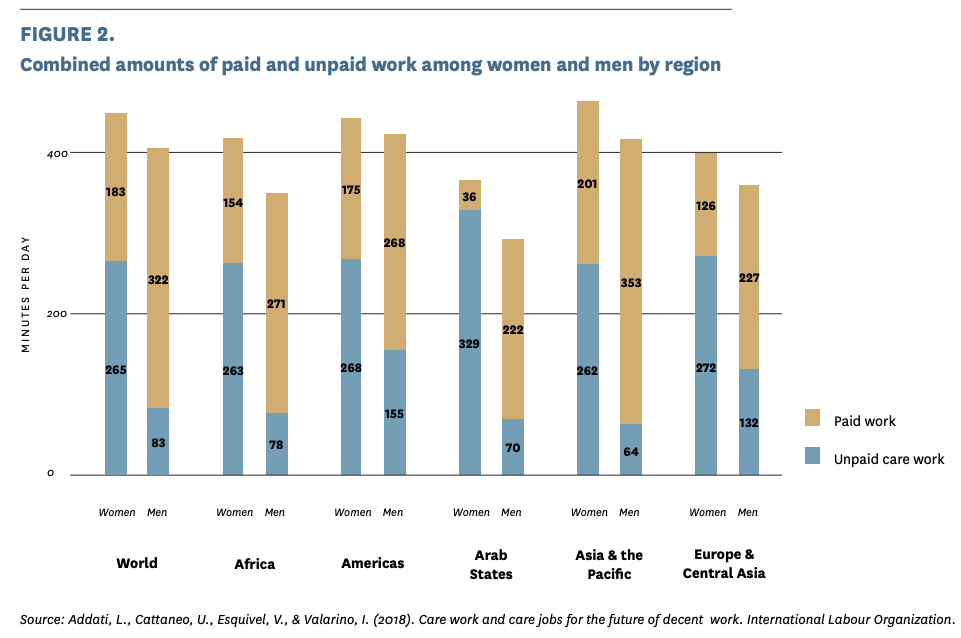

In early June Promundo launched its third State of the World’s Fathers report. The report shows that care work—like changing diapers, giving baths, feeding children—is viewed as women’s work. As a result, women spend up to ten times more time on unpaid care activities than men do. The report argues that if men engaged equally with women in unpaid care work at home, everyone would benefit. Women would be more empowered to participate in the workplace. Older sisters wouldn’t have to drop out of school (as documented in this recent article in Time). Children would benefit developmentally and boys would be more likely to believe in gender equality and share in unpaid work themselves. Men themselves also benefit: “Fathers who are involved in the home and with their children say it’s one of their most important sources of well-being and happiness.”

What can help to shift the balance so fathers play an increasing role in unpaid care work? A combination of new policies and new norms.

On the policy front, UNICEF’s call to action for family-friendly policies makes four concrete asks, including paid parental leave for both parents, breastfeeding support at work, high quality childcare services, and child grants.

On the policy front, UNICEF’s call to action for family-friendly policies makes four concrete asks, including paid parental leave for both parents, breastfeeding support at work, high quality childcare services, and child grants.

On the norms front, we can seize the moment when men become fathers. Because this is a big life transition, men are often open to hearing new ideas and taking on new behaviors. In the 2019 issue of Early Childhood Matters, also released in June, an article on Loving fathers, thriving children documents programs that engage new fathers in ways that improve child outcomes, increase father’s involvement in household work, and reduce domestic violence.

These are not the types of policies and programs that are typically associated with girls’ education. But shifting the dynamics around caring for young children can alleviate time constraints on older girls who might otherwise drop out of school. It can provide a stronger developmental foundation for very young girls and improve their schooling trajectory. And it can begin to promote more gender equitable outcomes for this generation and the next. The latest Facts About The Gender Gap in Education clearly show that “eliminating gender gaps in education does not produce equal life outcomes for women.” We might be able to intensify the impact of education on gender equality if we work more explicitly to change norms and put in place policies supportive of those changes.

Want to listen to one of the world’s notable fathers? Hear Ziauddin Yousafzai, made famous by virtue of being the father of Malala Yousafzai, reflect on “the power of parents in accelerating global education progress” in this podcast from Brookings.

Although fathers play a crucial role when it comes to girls’ education, focusing too much on fathers (and men and boys more generally), risks taking attention and resources away from marginalized women and girls. This tension is part of the reason that Pauline Rose and Louise Yorkeere from the REAL Centre at Cambridge have written a response to Evans and Yuan’s paper on What We Learn about Girls’ Education from Interventions that Don’t Focus on Girls. They draw out some of the nuances that get hidden in provocative headlines of the Evans and Yuan piece, most notably the conclusion that “there is an urgent need for more evidence on what type of interventions work to improve education for girls, where, how, and for which girls. This evidence needs to include evaluations of interventions that tackle the structural barriers to girls’ education.”