The Puggle: February 2023 edition

/ Aparajitha Suresh / The Puggle / March 13, 2023

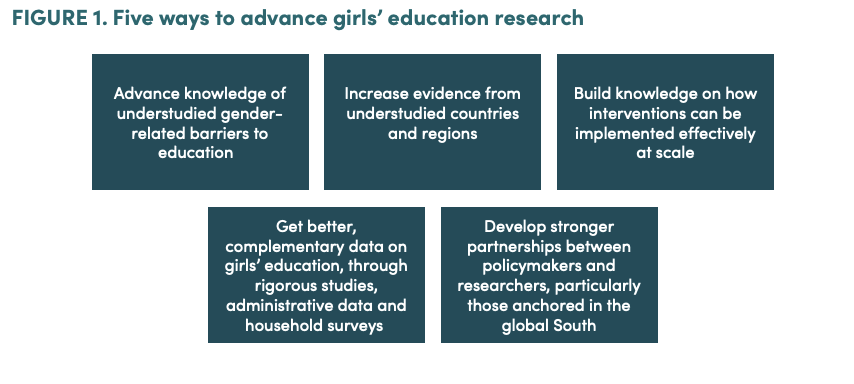

In February, researchers in the gender and education space coalesced to identify persisting gaps in our collective knowledge on girls’ education; gaps that, if filled, could significantly advance the girls’ education field as a whole.

A common, addressable trend underlies all five gaps: paucity of representative data. Below, we share two straightforward ways to support more inclusive data generation that can significantly strengthen the education field’s efforts to support all learners.

1. Implementing data disaggregation as an industry standard best practice

Disaggregating data by gender makes a difference. Over the past decade, the education field’s concerted focus to collect and monitor disaggregated enrollment data has allowed stakeholders to identify and support low performing geographies, enabling more than two-thirds of countries to close the gender gap in primary enrollment.

Echidna Giving’s founders have been long-standing advocates of data disaggregation + the transformational impact that could result “if every program, policy, or approach in international development simply counted girls.” Over the last decade, they have been part of larger efforts by like-minded philanthropies, national governments and multilateral institutions to influence the education sector to sustain a practice of disaggregating data that can help advance what we know about girls’ education.

Despite these concerted and sustained efforts, disaggregated data still remains distressingly rare to find. We have previously shared findings from a systematic review of how general education interventions specifically impact girls showing that nearly two thirds of general education intervention studies do not report gender-differentiated impact results. More recently, a 2023 systematic review of the evidence on learning during COVID-19 had planned to examine gendered differences in “learning progress during the pandemic, but found there to be insufficient evidence to conduct this subgroup analysis, as the large majority of the identified studies do not provide evidence on learning deficits separately by gender.”

The above evidence suggests an overt lack of gender intentionality in broader education research work. Disaggregating data isn’t difficult — but it does require recognizing that children of different genders might respond differently to the same intervention and building this consideration into the research design from the outset.

By failing to disaggregate by gender as well as for other high-risk identity markers (i.e. poverty, rural status, class, caste), the education field is missing out on critical opportunities to identify and address disparities that disadvantage those who already sit at the margin.

We need to make data disaggregation a standard practice across all research in education. We can also learn from the efforts of the labor field, which has recently integrated gender into its statistical methodology to uncover landmark new findings on gender-based inequalities in employment in time use, employment levels and the extent of the wage gap..

2. Prioritizing knowledge creation and data collection in/for/by underrepresented regions and populations.

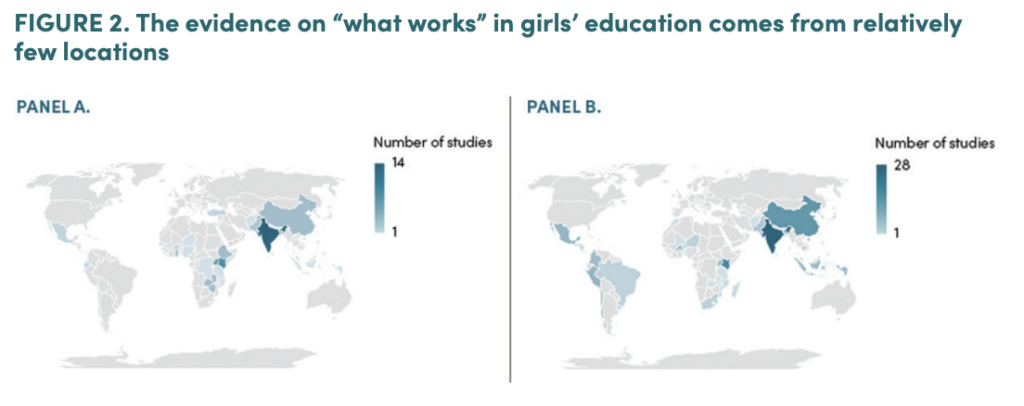

There are also striking geographic gaps in the evidence on girls’ education that significantly limit the field’s ability to understand the realities of girls from differing contexts, and thereby provide appropriate support.

Across countries, there is a significant concentration of evidence from larger middle income countries. While this is great for education programming within these countries, there is an alarming scarcity of evidence on how to support girls who live in low income countries, despite heightened need. From practitioners, we hear similar concerns of inadequate evidence within countries from marginalized regions — rural areas, tribal lands, conflict-affected settings, etc.

Another challenge is that research questions are often defined by individuals from the Global North. As this recent article highlights, “In areas of behavioural science that do have a stronger history of research in Africa, ‘research in Africa’ has meant taking African people simply as objects of study. Yet developing a robust behavioural science that works for Africa requires making room for African researchers — not merely studying African participants.”

To address these gaps, we have helped initiate a broader effort to more consciously support and strengthen Southern research ecosystems. Dana Schmidt presented on these efforts at the recent CIES conference, and if you missed that presentation you can view her slides here.

CSOs have also been working at the grassroots-level to fill these geographic data gaps through innovative new methodologies that are strengthening the local ecosystem. For example, Breakthrough’s school-based gender equity program mobilizes adolescent students as surveyors to first collect their own hyper-local data and make visible the gender discrimination they still experience, which they then use in their village-level campaigns for gender equity. Even here, large Global North-based research institutions can play an instrumental role in supporting such CSO-led data generation. IDinsight offers some powerful insights on how researchers can adjust their ways of working to better support and strengthen social movement organizations through strategic partnerships that emphasize co-creation and knowledge transfer.

Ultimately, while there have been significant advances in the amount of data and knowledge generated by the education field, there is still considerable ground to cover in terms of diversity and representation. The stark inequities that continue to manifest in education can be addressed, but only if we have the data to understand the ground realities of most marginalized peoples and geographies.