In honor of the New Year, in this edition of the Puggle we take a look at how we are progressing against our collective resolutions for education — as expressed in the sustainable development goals (SDGs).

In January, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics released an interactive SDG 4 Scorecard looking at how countries are doing against their benchmarks for seven Sustainable Development Goal indicators related to education. Here are five key takeaways based on our analysis of the scorecard, its accompanying report, and a few other key research findings released in January like the Annual Status of Education Report in India and Kenya’s latest Demographic and Health Survey:

1. Countries are making fast progress towards enrollment and completion goals.

At primary level, 48% of countries are making fast progress on completion and 50% on lowering out-of-school rates. In India, ASER 2022 results show that enrollment levels have climbed from very high (96.6% in 2010), to even higher (98.4% in 2022). Even better news is that enrollment rates are up from 2018 levels, which suggests that COVID did not disrupt the trend.

This heartening data suggests that communities value education and school systems are able to deliver it for increasingly higher proportions of children.

2. The only exception to fast enrollment gains is at upper secondary school.

This is the one level of education completion at which more countries have made slow or no progress than those making fast progress. This is particularly true for low and lower-middle-income countries; fewer than 10 countries in these categories have been able to make fast progress (Rwanda, Bangladesh, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Egypt, Ghana, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, and the Republic of Moldova).

More worryingly, roughly one third of countries have actually regressed between 2015 and 2020 when it comes to enrollment in upper secondary school.

3. Relatively few countries have set goals for gender parity, so it is hard to know whether the situation is improving for girls.

“The benchmark indicator with the lowest coverage is the gender gap of the upper secondary school completion rate.” Only 48 countries (23%) have set benchmarks for this. The report notes that this is because the indicator was only added in 2022, but it is time to make up lost ground!

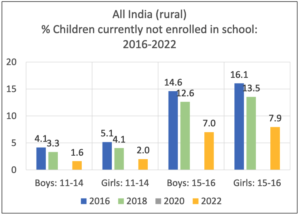

Among the countries who have set benchmarks, 39% are making fast progress, but 19% are making no progress. ASER showed that in India the proportion of children currently not enrolled in school has dropped since 2018, even for older girls — but the gap between girls and boys has not shrunk at all.

We need to push countries to develop national targets for gender equity. And to implement policies to reach those targets — here is another summary of how Sierra Leone is trying to harness a radical inclusion policy to do just this.

4. It is also hard to know whether countries are making progress toward learning outcome indicators.

Roughly half (or more) of all countries have no data related to important indicators like minimum proficiency in mathematics at the end of primary education.

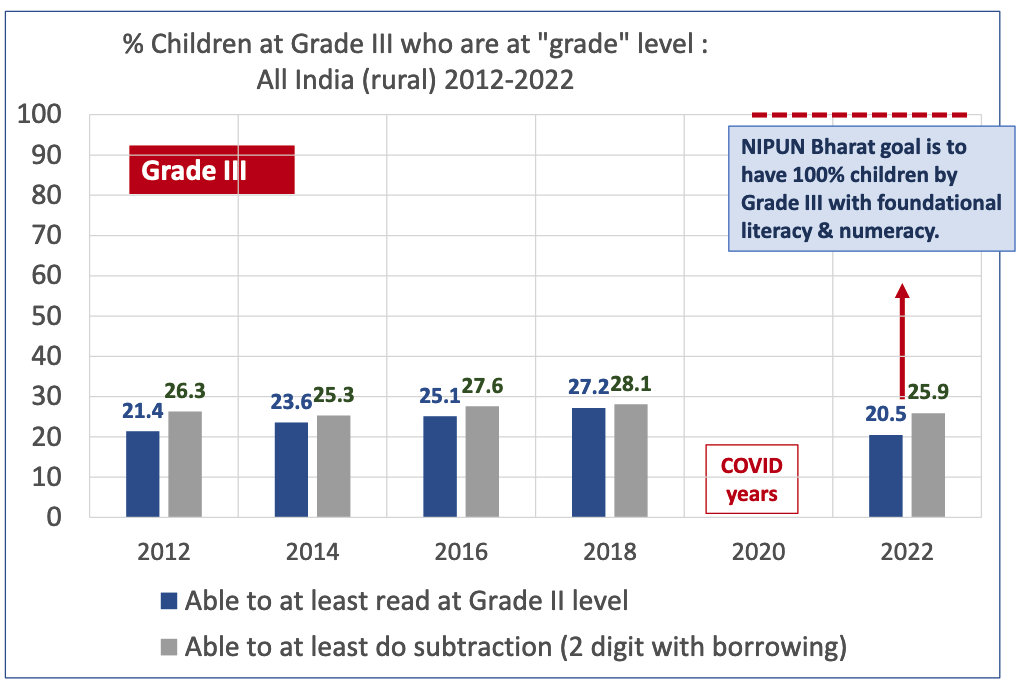

The data we do have on learning outcomes shows a clear negative impact of the COVID pandemic, unlike its muted effect on enrollment numbers. In India, ASER found that COVID disrupted the modest gains in learning outcomes that were happening in the pre-pandemic years. Only 20% of children in grade 3 are able to read at grade 2 level.

Reaching foundational literacy and numeracy goals will require a “big push,” as the ASER report points out. It might require looking not just at “learning loss,” but also how to support children in rebuilding their confidence, as discussed here. (And of course learning is not the only part of the schooling experience that matters. Check out the first in a series on lessons from the Girls’ Education Challenge on Ending violence in schools.)

5. Many countries have set benchmarks for pre-primary education, but not enough have policies in place for making progress.

72% of countries have benchmarks for pre-primary participation — making this the indicator with the least missing data. Most high-income countries are making fast progress against their benchmarks, as are 15 low- and lower-middle-income countries (Burkina Faso, Burundi, Bhutan, Cambodia, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, India, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Republic of Moldova, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Vanuatu and Viet Nam).

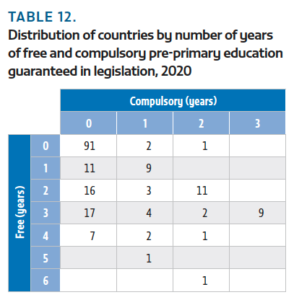

A deeper look at policies related to this indicator suggests countries have not yet put into place policies supportive of this indicator. The plurality of countries have not legislated any compulsory years of pre-primary and offer zero years of fee-free pre-primary education.

In the last 7 years, only 16 countries have increased the number of years of free and/or compulsory pre-primary education provided.

“Sub-Saharan Africa is also the region that is facing the biggest challenge with respect to both its starting point [on pre-primary education] and its population prospects. In the beginning of 2023, there were 70 million 4- to 5-year-olds in sub-Saharan Africa; by 2026, it is projected that sub-Saharan Africa will surpass Central and Southern Asia as the region with the largest cohort.”

Kenya’s latest Demographic Health Survey included an Early Childhood Development Index, which showed that 78% of children 2 to 4 years old are developmentally on track. Children who attend early childhood education are more likely to be on track than those who do not, as are children in urban areas compared to rural children, younger children compared to older, and children whose mothers have more years of education.

Not only do the early years matter for developing learning outcomes, Meenakshi Khanna points out in an OpEd for the Indian Express that reaching young children is also crucial in efforts to create [a] gender equal society. “Thirteen per cent of India’s population is between 0- 6 years old. If these children are exposed to gender-equal environments and content, they can potentially bring about significant change in society.”

Overall we have a bit of a mixed picture with respect to our SDG resolutions. Above all, it will be hard to reach resolutions we never set or review, so it is critical for countries to put in place benchmarks for gender equity and to consistently reflect on targets and the policies required to reach them.