July was a hot month—literally, with record-breaking heat in many parts of the globe, and figuratively, in girls’ education. The G7 and UNESCO hosted the Paris International Conference on Innovating for girls’ and women’s empowerment through education, where UNESCO launched an Atlas of Girls’ and Women’s Right to Education and France Calls on G-7 to Double Girls’ Education Funding in Africa’s Sahel.

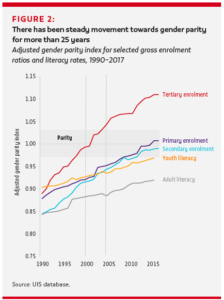

UNESCO also launched the 2019 Gender Review for the Global Monitoring Report. The report is indicative of a broader shift in rhetoric around girls’ education. In the 2003 Global Monitoring Report, which was focused on gender, the storyline was a pretty simple one of getting to gender parity in education enrollment and attainment. It was all about “equality in education.” This 2019 review, in contrast, is all about “gender equality in and through education” (emphasis added). It argues that schools must be “a place where gender stereotypes are deconstructed and fought.”

UNESCO also launched the 2019 Gender Review for the Global Monitoring Report. The report is indicative of a broader shift in rhetoric around girls’ education. In the 2003 Global Monitoring Report, which was focused on gender, the storyline was a pretty simple one of getting to gender parity in education enrollment and attainment. It was all about “equality in education.” This 2019 review, in contrast, is all about “gender equality in and through education” (emphasis added). It argues that schools must be “a place where gender stereotypes are deconstructed and fought.”

We think this is a necessary and welcome shift, but it also carries risks. First, it might create a perception that girls’ education advocates are constantly moving the goal post. Second, it’s hard to believe that “gender equality through education” alone is realistic when most high-income countries have achieved equality in education (if not watched women become better educated), but are far from achieving equality more broadly. Changes outside of education—in laws, business practices, norms, etc.—are also needed. Lastly, pushing for gender equality through education can create a backlash for girls, boys, and organizations who defy gender norms.

The Gender Review talks about how subject choice remains segregated by gender and harmful norms can prevent change from happening in education. This recent recent talk at the Center for Global Development on what works to empower women economically reminded us that subject choice has real economic consequences: segregation in career choice across men and women is a strong driver of unequal economic outcomes. Furthermore, teachers are the “kiss of death” for their students’ career choice, because they encourage female students to take on gender-conforming roles.

Although the report talks about learning outcomes for girls vs. boys (girls are stronger in reading, in part because parents read more to daughters, and boys are stronger in math), it is largely silent on what schools should be teaching in order to advance equality through education. It does argue that “comprehensive sexuality education expands education opportunities, challenges gender norms and promotes gender equality” (this report argues for how in detail). But as the same panel cited above reminded us, there may be a wider set of skills and mindsets that are especially critical for girls. In providing business training for women, shifting mindsets was critical, not just teaching technical business skills. Other recent research in Zambia finds that negotiation training significantly improves educational outcomes for girls in a lasting way. And this recent report out of the Partnership to Strengthen Innovation and Practice in Secondary Education (PSIPSE) highlights how to best support youth to acquire the knowledge and skills that will allow them to thrive in school, work, and life.

For the first time the Gender Review looked at how donors tackle girls’ education. “$4.2 billion, or half, of total direct education aid included gender equality and women’s empowerment as either a significant or a principal objective.” For Canada, a full 92% of its aid to education was deemed gender-targeted. This is really significant. It means that donors are arguably putting more concerted attention on gender than governments. All the more reason that their aid should target the most effective strategies for improving girls’ education. Perhaps looking at how well donor aid (and education sector plans) performs in that regard will be the focus of a future report.

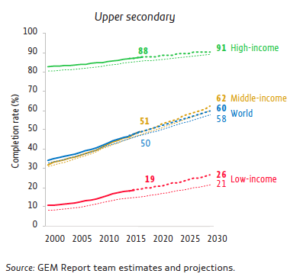

UNESCO launched a second big report in July looking at whether or not countries are on track to meet SDG 4 (the report is nicely summarized here and here). It provides a compelling case that we need to be doing things dramatically differently today in order to hit all of the SDG education targets for the generation now entering school, who should finish secondary school by the 2030 SDG deadline. To take just two dramatic findings:

- “The world will approach the learning target only if progress equals the rate of the best‑performing countries”

- At upper secondary, 60% of kids in low-income countries are out of school. Worldwide only 50% of kids complete upper secondary education. This drops to a mere 19% in low-income countries. We are very far from achieving 100% completion of secondary.

In the face of these shortcomings, what should countries prioritize first? SDG 4 includes 43 laudable indicators for education, but how should countries navigate the tradeoffs between investing between them? This seems like a necessary conversation in the face of the report’s findings.

Also, this month, don’t miss the first round of blog posts from the newest cohort of Echidna Global Scholars!