It’s now been more than 140 days since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. It’s clear that there is no going back to normal anytime soon, and that instead we are faced with adjusting to new normals that are rapidly changing. What does this mean for the education sector and for girls’ education in particular? The story we’re piecing together has four themes:

- Education is in crisis. In fact, it faces more than one crisis.

- The crisis is especially bad for girls.

- The pessimistic view is that it will take a long time to recover and inequality will be starker for many years to come.

- The optimistic view is that we’ll “build back better.”

In the remainder of this post we pull together what we’re hearing and reading on each of these themes. Please let us know in the comments what we’re missing.

Education is in crisis. In fact, it faces more than one crisis.

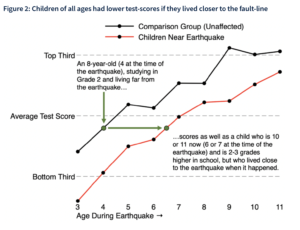

For the first time ever education systems are faced with the double shock of prolonged school closures and a massive economic downturn. As of this writing over 1 billion learners are still out of school. What we know from past crises is that these prolonged periods out of school will leave a mark. Jishnu Das, Benjamin Daniels, and Tahir Andrabi looked at what happened to children whose schools closed for about 14 weeks following the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan. In short, they found that “children who lived closer to the fault line were doing worse than those who lived farther away. These gaps were large and represented the learning-equivalent of around two years of schooling” (emphasis added).

The authors also found young children and those in utero at the time of the crisis were stunted. Both findings portend lower future earnings for these children. The World Bank has estimated that a 5 month school closure will result in $16,000 lost potential earnings per student, or $10 Trillion (8% of global GDP) for this generation, which will also be strapped with the debts being accrued to handle the current crisis.

On top of not being in school and not getting the nutrition they need, children are facing increased violence at home, which will further stunt their development. Even in the best of times only 18% of caregivers use only nonviolent discipline. With children spending more time than ever with parents who are under tremendous stress themselves, this is only getting worse.

Equally scary is how all this will be compounded by the economic crisis. For example, we’re seeing a potential reversal of ten years of progress in Africa and a battering of the middle class that will take a long time to recover. Mark Lowcock and Masood Ahmed argue that the developing world faces a health, economic and security crisis that will dwarf the impact of Covid. The G20 isn’t doing much to “mitigate what will be the deepest economic recession in three generations and the risk of reversal of decades of development.”

This crisis is especially bad for girls.

The gains to girls’ education are recent and fragile as it is—for example, in India education doesn’t lead to better labor force outcomes or marriage prospects, which makes investment in education a tenuous prospect for families. As many have argued, progress on girls’ education is also at risk of being pushed back by several decades. Four strands of disadvantage stand out in particular:

- Violence. In a survey of frontline providers, the Center for Global Development found 66% of respondents felt that gender-based violence (GBV) was a very important concern. This seems to be for good reason—calls to helplines in Kenya have increased 10-fold since the March lockdown began.

- Pregnancy and early marriage. Linked to this are concerns about increased pregnancy (particularly in Africa, where environmental risks are ripe for this) and early marriage (particularly in South Asia, where reports of child marriage are already up).

- Caretaking responsibilities. Girls shoulder a disproportionate burden of caretaking responsibilities, which means caring for younger siblings who are also out of school. We’ve heard reports that demand for childcare is down because older sisters are home from school and taking on this role.

- Less access to technology. Even when families have the technology needed to access distance learning (which is not frequent, as we detail in the section below), boys are given preferential access (as the Population Council has already found in Kenya, for example). In countries like India, boys are also more likely to be enrolled in private schools who have the infrastructure to offer more comprehensive distance learning opportunities.

As a result of all of the above, girls are less likely to learn at a distance while schools remain closed, more likely to suffer mental health impacts of the pandemic, and less likely to return to school when it reopens. In Sierra Leone, girls’ school enrollment dropped from 50% to 34% after the Ebola crisis. In a recent survey of girls in their program, Room to Read found 50% of girls are at risk of remaining out of schools when they reopen.

These dynamics above point to urgent needs to:

- Combat GBV, including through evidence-based approaches like safe spaces

- Ensure equal access to technology

- Put in place efforts to re-engage girls in education, like incentivizing parents to prioritize investments in girls through conditional cash transfers, uniforms, school meals, etc.

The pessimistic view is that it will take a long time to recover and inequality will be starker for many years to come.

A big and prevailing concern is that investments in education will drop both in absolute and in relative terms. This is the first of Shelby Carvalho and Susannah Hares’s six dire predictions on how COVID-19 will shape the future of education. Early Childhood education may suffer the most, because investments in this space are more recent and precarious.

A reliance on technology as a strategy for teaching and learning while schools are closed will inevitably widen the gap between those who have access and those who do not, both within and across households. Carvalho and Hares also document that in low and middle-income countries, only 20% of households have access to the internet and only 50% to TV or radio. A World Bank working paper finds that only half of students with access to TV-based learning in Bangladesh choose to watch them, and of the only 21% of children who can access online learning programs, a mere 2% choose to do so. Furthermore, because learning is social, we still don’t know how much students will learn without that element. This is particularly true for younger children, as Sarah Kabay, Olga Namen, and Stephanie Wu from IPA thoughtfully document in a post on distance learning. Children in homes where parents can provide extra support will no doubt fare better than those relying on technology alone.

The Pakistan results described above are also instructive. There, researchers found that “The children of mothers who were somewhat educated were fully protected from the disruption of the earthquake, so that all the losses were felt by those whose mothers had no education” (emphasis added). (This is, of course, a good case-in-point for the importance of girls’ education!)

In short, we’re looking at learning loss for the poorest students while their better-off peers continue to make learning gains and the wedge between the two grows ever larger. Our solutions and programs must obsessively push for more equitable outcomes.

The optimistic view is that we’ll build back better.

Winston Churchill famously advised “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” Crises provide an opportunity to do things in ways you didn’t previously think possible. In the context of this crisis…

- Sierra Leone’s education minister, David Sengeh, “sees the pandemic as an opportunity to ensure that everyone, everywhere, gets a good education. Covid-19 has given the government the “oomph” it needs to make it happen.” Since the outbreak, Sierra Leone has passed 6 transformational policy agendas, including incentives for girls to stay in school (cash transfers, access to technology) and a new curriculum framework focused on 5C’s (civics, computational thinking, comprehension, creativity, critical thinking).

- Parenting is now front and center on everyone’s minds, because even prominent ministers are faced with the prospects of dealing with their children 24/7. Folks active in the parenting space have used this as an opportunity to scale-up effective parenting programs in over 100 countries to try to tamper violence against children.

- There are opportunities for system reforms that are responsive to the crisis and simultaneously tackle challenges that have plagued the system for a long time. For example, focusing on foundational skills, teaching at the right level, and paring back overburdened curriculum. Modeling by Michelle Kaffenberger suggests that doing exactly this sort of remediation and realignment of instruction can counter the shock of the pandemic and help children learn even more than they would have otherwise. And Angrist et al find that some of these interventions can be effectively provided via low-tech interventions even during the pandemic.

- Similarly, education ministries have started questioning how fair high stakes exams are in light of the pandemic—this may lay the groundwork for reconsidering the role of such exams, which are inequitable under any circumstance.

- Education systems will also have to find ways to support student mental health and wellbeing — again, a problem that has arguably faced many students in the system regardless, but is now receiving more attention. A study by Dream a Dream found that 96% of schools in Karnataka were concerned about this issue, and organizations like theirs have begun to think about “what if” we could reimagine schools in light of the crisis.

- More broadly, can the pandemic help catalyze change that we thought would take decades to come? Will any of the innovations catalogued in the newly-relaunched Center for Education Innovations help serve as inspiration for re-imagined systems? As organizations like Educate! pivot to play “offense” in addressing the crisis, what new ideas might emerge and stick?

Let’s hope (and work towards!) this optimistic view. A lot depends on it.