June was jam-packed! If you had trouble staying on top of all the education-related news (we certainly did…) this update is for you. We’ll jump right into it.

First, we highlight four important publications from June which collectively provide a pretty comprehensive — albeit depressing — synopsis of the state of education right now.

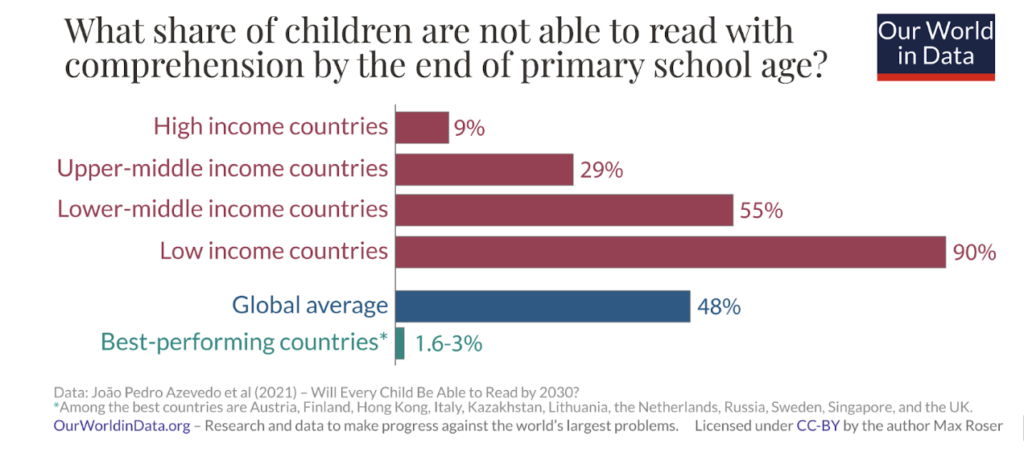

Our World in Data synthesized research looking at how the world could provide a better education to the next generation. Their analysis shows that the share of children unable to read by the end of primary age is alarmingly low — but it doesn’t have to be that way. “The world has made big strides in getting children into schools. These children are no longer isolated; teachers are in contact with them. At the same time, researchers have identified low-cost ways to improve their learning outcomes. Taken together this gives us the possibility to turn schooling into learning.”

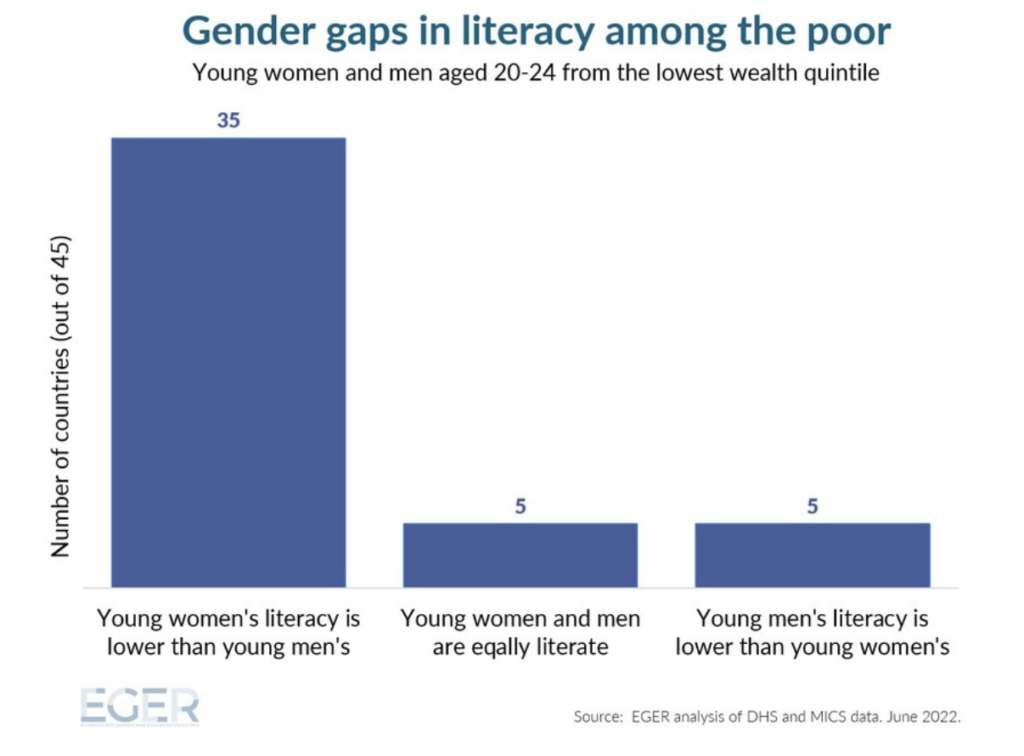

Although it provides a useful overview, Our World in Data does not touch on gender gaps. Lest you are left with the impression that girls are performing just as well as boys, the Population Council’s GIRL Center draws on its Evidence on Gender and Education Resource (EGER, for short) database to dispel this myth. The newly-launched Power in numbers shows, for example, that “While gender gaps have decreased in many countries overall, among the poor it is still girls who are often the ones missing out.” Their underlying database is available for anyone to use — dive in here!

Echoing many of the key messages from Our World in Data, the World Bank’s updated State of Global Learning Poverty report finds staggering rates of learning poverty in 2019, before the pandemic hit. It also suggests that “global progress against learning poverty had already stalled: between 2015 and 2019, there was no reduction in global learning poverty.” In an accompanying blog and Guide for Learning Recovery and Acceleration, the World Bank offers a “menu of policy options” for ensuring “effective approaches for promoting foundational learning reach all children and youth.”

Looking at the commitments countries have made to alleviate learning poverty and meet the sustainable development goals for education (SDG 4), UNESCO finds that “almost 9 in 10 countries have made a clear statement on their contribution to SDG 4. Unfortunately, these statements confirm that by 2030, even if countries succeed in their efforts, the world will fall short of the ambition to achieve universal education…only 1 in 6 countries will come close to having at least 95% of their youth completing secondary school. Less than two in three children are expected to complete primary school and achieve minimum learning proficiency by 2030, leaving 300 million without these skills.”

UNESCO also published its Education finance watch 2022, finding that the share of spending on education budgets is lower than 2019 levels in low-and lower-middle-income countries and that 43 bilateral donors decreased their aid to education. Households in the poorest countries are shouldering “three times more of the share of the cost of education than in the richest countries.”

Next up, a round-up of news from the Transforming Education Pre-Summit that was hosted in Paris in June.

Given the reports above, it’s no wonder that at this year’s UN general assembly meeting the UN secretary general is convening the Transforming Education Summit, “to renew our collective commitment to education and lifelong learning as a pre-eminent public good.” In June, the Transforming Education Pre-Summit allowed key stakeholders to share what transforming education means to them. The summit events, summarized here, urged “Heads of State and Government to push education to the top of the political agenda.”

Although not covered in the summary, the summit featured rich discussions on gender transformative education, illustrated here. Young people were also invited to share their views (some through spoken word), but David Moinina Sengeh, Minister of Education and Chief Innovation Officer from Sierra Leone, argued that they should have had an even larger role as part of decision making.

Elsewhere, in a piece for Project Syndicate on How to Get Girls into School, David Moinina Sengeh describes how his ministry invites marginalized young people to help set the agenda and make decisions through a youth advisory group. Separately, he and Rebecca Winthrop from Brookings look at Transforming education systems: Why, what, and how. They argue that: (1) “the world is at an inflection point,” making transformative education an urgent agenda (that’s the “why”); (2) education system transformation is about ensuring the goals of an education system meet the moment and system components coherently contribute to those goals (that’s the “what”); and that (3) it can be achieved through a shared purpose, redesigned pedagogy, and “positioning and aligning all components of the system to support the pedagogical core and purpose” (that’s the “how”).

Coming out of the Paris deliberations, Ministers of Education from over eighty GPE partner countries committed to transforming education by (a) mobilizing political will to fund education; (b) using evidence to prioritize “key policy reforms in and out of the classroom that put the learner at the center;” and (c) following the Freetown Manifesto for Gender-Transformative Leadership in and through Education to hardwire gender equality in education. In turn, they asked the international community to provide more efficient aid towards national priorities, to mobilize more resources (including through debt reduction!), and to help address context-specific issues (like the adverse impacts of climate change and education in conflict and crises).

Lastly, we offer some pretty interesting research findings that were published and/or publicized in June.

The long-awaited and hotly-debated findings from a randomized control trial of Bridge International Academies in Kenya were published in a working paper. Owen Ozier offers a nice summary here, highlighting how “Two years at Bridge International Academies increased test scores by 0.89 additional equivalent years of schooling (EYS) for primary school pupils and by 1.48 EYS for pre-primary pupils.” The authors conclude that these large learning gains are driven by “Bridge’s approach to standardization, featuring detailed scripting, intensive monitoring, and more”.

The study offers limited evidence on important dimensions like “Bridge’s compliance with the national curriculum, working conditions and pay for Bridge teachers, registration of schools, and student safety in schools.” The authors do find very high rates of corporal punishment (77%, compared to 83% in public schools) and playing field hazards (30-40%, higher than at public schools). While the learning gains are powerful, on these dimensions and others, Bridge International Academies falls short.

When it comes to government curriculum reform, Daniel Rodriguez-Segura and Isaac Mbiti find that Tanzania’s 2015 pivot to focus 80% of instruction in Grades 1 and 2 on the “3Rs”—reading, writing, and arithmetic—increased reading and math scores by around 0.20 standard deviations one year after the reform and decreased dropout rates of children up to four years later.

Lekha Subaiya and Amy McLaughlin argue that “The biggest challenge in understanding children’s lives comes from data collection structures that do not embed data about children in the data about their families.” We cannot adequately understand what is happening for children without understanding what is happening in their families.

That’s one reason why it is so exciting to see researchers from the Center for Global Development encourage researchers looking at early childhood development programs to measure the impact of interventions not only on children, but also on their mothers. They’ve compiled a set of instruments that have been used to measure maternal mental wellbeing in low- and middle-income countries, identifying where they have been used and validated.

For the same reason that understanding what is happening in families can help us understand what is happening with children, working with those communities can be a catalyst to tackle disrupted learning. Rukmini Banerji from Pratham and Asif Saleh from BRAC share experiences working with communities during COVID, and argue that “Schools should welcome community members and see them as the source of innovation, inspiration, and support that they have proven to be. The people closest to challenges are the best positioned to drive solutions, and people in communities know the future of their communities lies in their children.”

If you missed RISE like we did this year, then you must read this round-up of 30+ findings from David Evans. Here is a small teaser of some presentations that intrigued us:

- Yue-Yi Hwa shared that what teachers do in the classroom is determined by: (a) what they value, (b) what they think is feasible, and (c) what they believe is expected. You need to push one or more of these levers to shift teacher norms (key slides).

- Kaffenberger and Pritchett offered a conceptual framework on the drivers of educational system performance that suggests that “commitment to the purpose of learning is a critical missing link to addressing the learning crisis.” This is not always the purpose of education systems, which may focus on educating elites or have contested purposes.

- Bano described how communities in northern Nigeria support Islamic and Quranic schools in part “because state schools fail to deliver quality education, they promote out-of-reach aspirations (the expectation of formal sector employment), and they promote liberal values around gender, sexuality, authority, etc.; values which directly clash with communities’ religious or moral preferences.”