The Puggle: July & August 2023 edition

/ Dana Schmidt / The Puggle / August 30, 2023

The Global Education Monitoring Report was released in July. It finds that “In recent decades, progress on girls’ education access and completion has been one of the main achievements in equality in education,” noting that “all regions have achieved gender parity in education except sub-Saharan Africa, where there are 90 girls enrolled for every 100 boys.” It also finds that “girls’ learning has improved faster over time than that of boys,” with girls consistently outperforming boys in reading.

A World Bank study on The Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 on Adolescents’ School Attendance in Sub-Saharan Africa found that “there is no evidence to suggest that gender gaps widened during the pandemic. If anything, gender gaps appear to have narrowed in some countries.” Meanwhile, in Bangladesh, “Slow recovery from the pandemic for poorer households has increased barriers to education access, with more boys than girls dropping out of school and rural students continuing to be outperformed by their urban peers.”

What are we to make of this latest evidence? Should we de-emphasize a focus on gender and education?

Our answer is an emphatic no. We absolutely should celebrate the success achieved — which is itself perhaps the best proof of the importance of tracking and attending to gender gaps in education. But we cannot claim victory for at least three reasons:

- The story of gender parity (or advantages) for girls masks other inequities in education.

- We cannot be satisfied with girls’ gains in education when they are not translating to broader social equality.

- The systems of oppression that stymie girls in education stymie boys as well.

We cover each of these challenges in more detail below, highlighting the latest data and evidence behind each of them. We also offer thoughts on what to do about it.

The story of gender parity (or advantages) in education for girls masks other inequities in education.

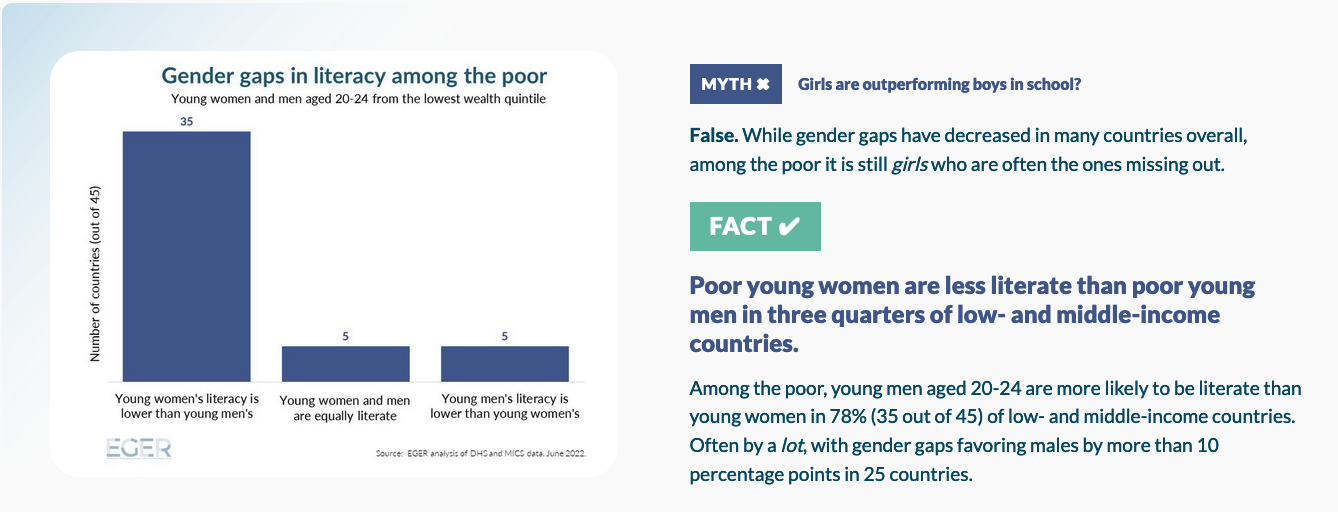

As noted in the Population Council’s Evidence on Gender in Education Resource (EGER) work, the closing of gender gaps more broadly masks more marked gender gaps among specific populations. Girls from poor households, rural communities, and other marginalized groups are often still more likely to miss out on education than their male peers.

Although the pandemic’s effects on girls were not as sweeping as many feared, as we have discussed, adolescent girls were much more affected. Returning to the Global Education Monitoring Report, it highlights the gendered impacts of COVID-19 on learning in Pakistan, where the “reading gender gap reversed between 2019 and 2021 from favoring girls (18% boys vs 21% girls) to favoring boys (16% boys vs 14% girls).”

In short, population-level gender parity in education data masks gender inequities among specific populations of girls. (Also of interest is how data can distort gender gaps: a recent study looking at The Link between Gender Gaps in School Enrollment and School Achievement shows that when girls and boys enroll in school at different rates, whichever group is less well represented in school will be made up of relatively more advantaged students and therefore show an advantage on learning achievement that would not exist if their less advantaged, out-of-school peers had been enrolled.)

New research out of Young Lives’ longitudinal studies in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam also suggest that gender parity on certain outcomes (like school enrollment and completion) masks gender gaps on other outcomes, like socioemotional skills associated with empowerment. These gaps emerge in late adolescence, when boys begin to score more highly than girls on skills like self efficacy and agency in particular. The gaps are widest for students from the poorest households. “The authors conclude that gender differences in socioemotional skills probably emerge as the result of cultural norms.”

A separate policy brief underscores how consequential these results are, given that social and emotional skills are important for a wide range of life outcomes. Targeted support to improve girls’ and young women’s social and emotional skills can make a difference for their well-being and life outcomes.

We cannot be satisfied with girls’ gains in education when they are not translating to broader social equality.

Even when girls are achieving as much as boys in education they are not achieving equality in society. Further research from the four Young Lives’ countries shows that “women earn significantly less than men…even after accounting for differences in carefully constructed skill endowments.” A related policy brief underscores that “improving skills and educational outcomes may not translate into increased women’s participation in decent paid work without addressing country-specific barriers to gender equality.”

As much as girls might gain from education, there are also things that they give up. This is intimately highlighted in Xanthe Scharff’s piece describing her return to Malawi after starting an effort to support girls’ education there 18 years ago. She shares how girls supported with more education are also subjected to “taunts and condemnation” for being different. Further support for girls to develop their agency, not just knowledge and skills, can help to buffer some of these challenges. Girls gaining equal access to education is critical; but we cannot be satisfied that it is sufficient until it translates to broader social equality.

The systems of oppression that stymie girls in education stymie boys as well.

If we point to increased parity in education outcomes for girls as a reason to ignore gender and education altogether, we would be ignoring forces that are harming students of all genders. The patriarchal systems that stymie girls’ education outcomes and hamper their ability to achieve broader equality even when they are educated are also harmful to boys and men.

One of the reasons girls’ outcomes were not as bad during the pandemic as was feared was not because girls’ education was not suffering, but because boys were suffering just as much. While patriarchal systems put pressure on girls’ to marry in the face of economic hardships, they put pressure on boys to find jobs.

The latest State of the World’s Fathers report finds that “in the Global South, women do 3 to 7 times more” unpaid care work than men. But women and men speak about how caring for their families brings them happiness and well-being. Social norms are preventing men from engaging in caregiving that might allow for better mental health and greater satisfaction in life.

As Malala so powerfully said on the occasion of her birthday:

“I believe that so many of the problems girls face would be solved if we could break the stranglehold of patriarchy — the misogyny we disguise as “culture”, “tradition” or “religion.”

We need fathers like mine who stand up for their daughters’ rights. We need mothers who speak up for them and brothers who celebrate their wins. We need imams and priests who speak out against those who twist our faith to hold women and girls back. We need a community of people who do not tolerate any harm or discrimination against girls and protect their equal rights. And each of us must begin at home by challenging our own thoughts and by starting conversations with our family members and friends.”

This would make the world a better place for everyone, not just for girls.

So if we cannot walk away and claim success on gender parity in education, what should we be doing? We highlight three ideas below:

- Support improvements in the education system — and track that they work for everyone

- Consider not only what works for children, but how our efforts support (or detract from) gender equity in their homes as well

- Use education as a vehicle for critically analyzing and shifting gender norms

We should support improvements in the education system — and track that they work for everyone

If girls go to school in systems that produce equal outcomes for boys and girls but everyone is doing terribly, nobody wins. We need to continue to pursue improvements in education systems — e.g. by investing early, teaching reading in students’ home language, improving school management, and offering arts education, to cite research examples from recent months — and we need to design these solutions and track their impact with gender in mind.

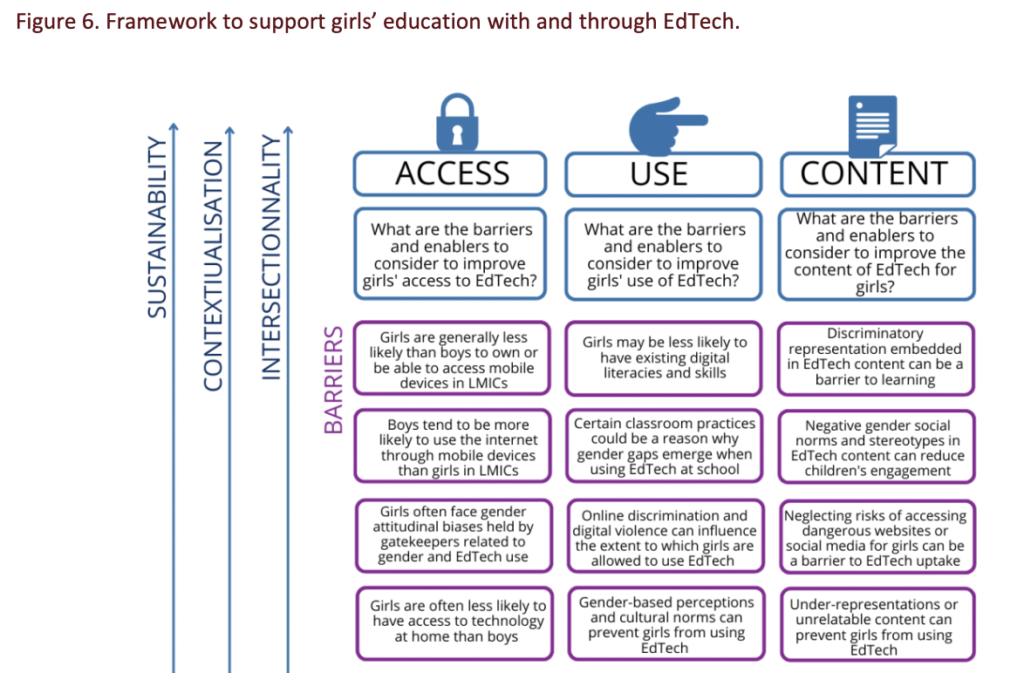

A good example for how to consider gender in design and measurement comes through in the background note for the Global Education Monitoring Report on Gender equality and education technology. The authors describe the gendered barriers in EdTech that “without careful consideration…could exacerbate existing ‘digital divides’ and increase inequity.”

We should consider not only what works for children, but how our efforts support (or detract from) gender equity in their homes as well

Designing education interventions to serve girls and boys alike is a good start, but we may be leaving impact on the table if we stop here. Consider the example of a pre-primary education program offered to young children for three hours a day. It has been designed with a gender-sensitive curriculum and the teachers are well-trained to include children of all genders in all types of play. But the hours of the program are so short that older sisters responsible for caring for young siblings in the program cannot attend school themselves.

As I argue with my co-authors in this recent OpEd, those of us working on early childhood development with children in mind must also “attend to the needs of women and families as they determine when and for how long childcare centers will be open, where they are located, and how well childcare providers, often women themselves, are paid. They should think about gender training and engaging fathers or male family members to ensure equity and to optimize impact for mothers and children.”

We should use education as a vehicle for critically analyzing and shifting gender norms

Education can do more than just close the gap between girls and boys on school access, enrollment, completion and learning. We can and should “utilize the whole school system — from policies to pedagogies to community engagement — to transform stereotypes, attitudes, norms and practices” around gender, as Sohini Bhattacharya, CEO of Breakthrough, so passionately argues in the first edition of Engendering Education. This magazine aims to “build an inspired community that wants to contribute to a movement that can address gender inequity and inequality at its roots.”

If you’re looking for proof that this is possible, the UN Girls’ Education Initiative has compiled evidence from thirteen programs that address gender stereotypes through schools. These cases demonstrate that programs can end gender stereotypes and achieve results surprisingly quickly and outlines some of the keys to success.

As highlighted in a National Geographic piece, “Everywhere, people have always pushed for their societies to be structured differently, for the oppressed to have more freedoms or privileges…Globally, impassioned movements for gender equality—sometimes tipping into violent protest—indicate that patriarchy is not as stable as it seems.” School systems are one way to shift these systems.

It’s hard to believe that we’d have even more to say, but…

- If you’re interested in evidence-based practices for parent and caregiver support, check out a new online global platform with lots of research and resources.

- If you would like to enhance your think tank and leadership skills, applications for the School for Thinktankers are open now.

- If you want to nerd out on the cost effectiveness of education interventions relative to health interventions, check out this analysis on the effective altruism forum