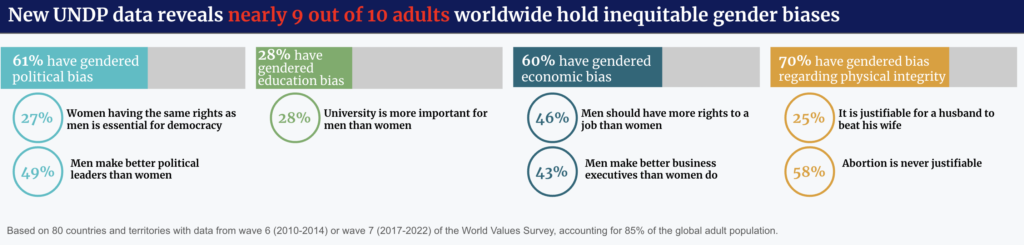

June was jam-packed with new data on the global state of gender equity. The month kicked off with the UN Development Programme’s (UNDP) second update to the Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI), which found that 88.69% of adults still hold at least one inequitable gender bias — and that the majority hold multiple.

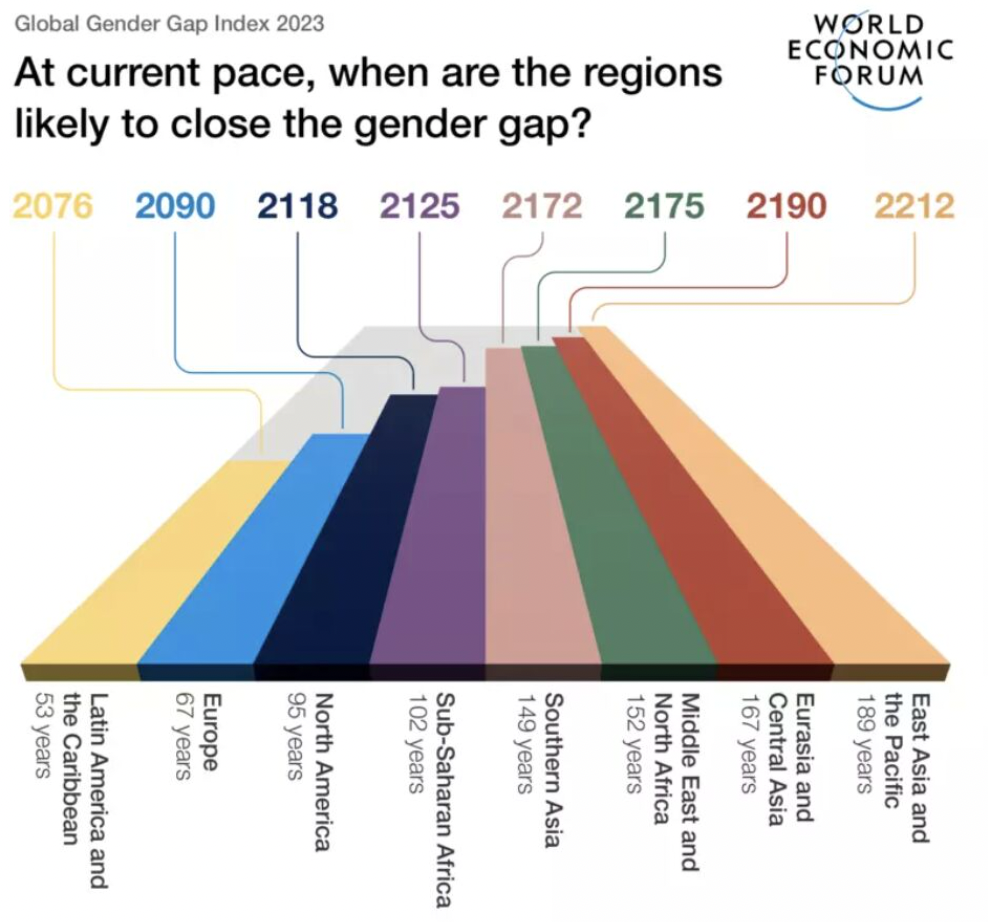

Soon after, the World Economic Forum released the 2023 edition of its Global Gender Gap Index, an annual benchmark of progress towards gender parity across economic, educational, health, and political outcomes. The new data reveals that progress towards parity is slowing down:

At the current pace, it will take 131 years to reach full gender parity, meaning that children born today will likely never live in gender equitable societies. This is especially true for children in the Global South, who experience heightened levels of gender inequity (in terms of both bias and parity) thanks, in part, to the legacy of colonization.

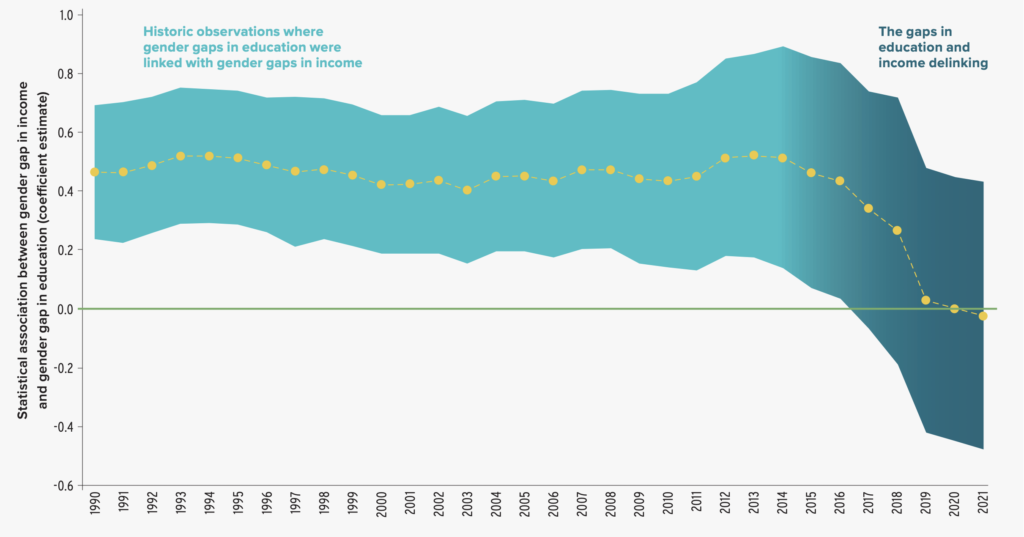

Critically, both reports underscore a diminishing influence of education on later-life gender equity.

Historically, there had been a robust empirical link between education and income — as gender gaps in education declined, so did gender gaps in income. This motivated the development sector to focus significant efforts on gender parity in education, expecting this to reduce income gaps in the long-run. Yet despite closing 95.2% of the gender gap in education attainment, women still remain markedly behind in terms of labor force participation and income earning ability, serving as an important reminder that parity in access alone cannot suffice to uproot harmful gender norms and practices that continue to constrain girls’ and women’s mobility, choices and opportunities.

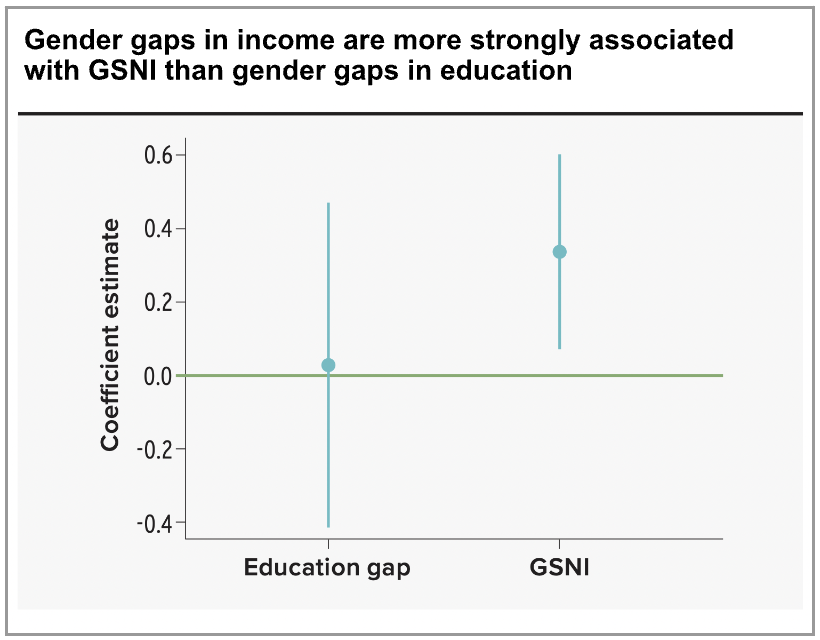

Now, the UNDP finds that the gender wage gap better correlates to gender bias levels (as measured by the GSNI). This could be because the GSNI correlates well with the inequitable distribution of care and domestic work, which accounts for most of the recent variation in the gender wage gap. Take the example of India, where female labor force participation has been declining despite advancements in education parity. This study by Mobile Creches examines how high-quality affordable childcare provision can support more women to join the workforce by removing the tradeoff between employment and their child’s development. The study notes that among women accessing childcare, those who had higher levels of education were more likely to find employment in the formal sector which offers better working conditions, security, benefits and wages than found in the non-formal sector.

Equal access to education is important in its own regard: as a basic right we owe to all girls; and as a proven strategy through which countries can achieve improved social, economic and health outcomes across generations. But improving access without tending to the quality of learning and the harmful beliefs and practices that prevented girls from accessing education in the first place can only achieve so much.

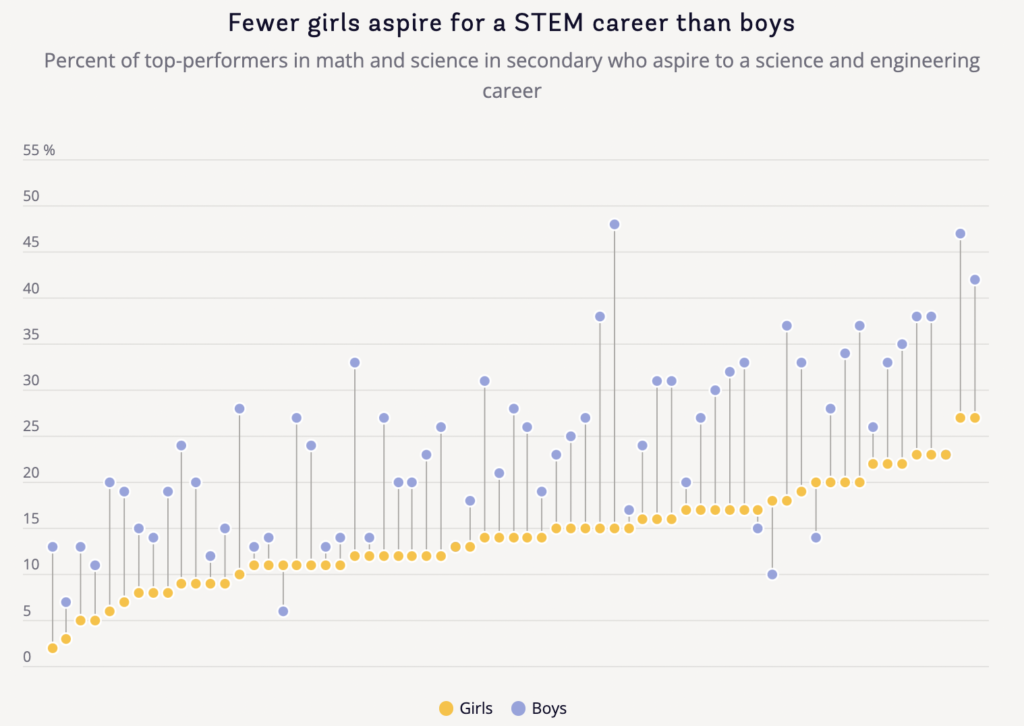

One area within education where it is clear that parity does not translate into equity is in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). The 2023 Sustainable Development Goals Atlas visually highlights how even among the best educated students, girls are less likely to aspire for a career in STEM — an outcome that has been attributed to how schools, families and societies continue to socialize children in gender stereotypical ways. Recent research from UNESCO illustrates how this manifests in early learning: Although parents report spending more time on girls’ early numeracy education, they tend to involve girls in basic activities like counting objects. On the other hand, parents are more likely to engage boys in activities that require higher order spatial skills, such as playing with building blocks or construction toys, which are important predictors of later mathematical competence.

The widespread prevalence of school-related gender-based violence (SRGBV) is yet another example of how achieving parity in enrollment or learning is not enough to safeguard girls and children of other marginalized gender identities from the harms of inequity. While multilateral and national efforts to monitor and address SRGBV are emerging, global attention outside of the gender space still remains low.

The good news is that there is already a movement afoot to push gender work in education towards true transformation of how societies give meaning to gender. Gender Transformative Education, or GTE for short, is an emerging area of practice that seeks to equip students with the skills and knowledge necessary to challenge and uproot harmful gender norms and practices that perpetuate gender inequities within education, and through this, in broader society.

If you’re interested in joining the GTE movement, be sure to register your interest for the 2023 Feminist Network for Gender Transformative Education convening, which will bring together civil society, researchers, funders, multilateral partners and government representatives to collectively plan how to advance GTE around the world. The event is hosted by the United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative and will take place in Istanbul from November 2-3, 2023.

For those of you who are already conducting cutting-edge GTE programming, do check out this recently launched Knowledge and Innovation Exchange (KIX) call for proposals for applied research projects to build evidence on contextualizing and scaling programs aiming to promote gender equality and social inclusions in schools. Submissions are due by August 28th.