In March, we celebrate International Women’s Day. Alongside the celebration come lots of reflections on how well the world is progressing towards gender equality.

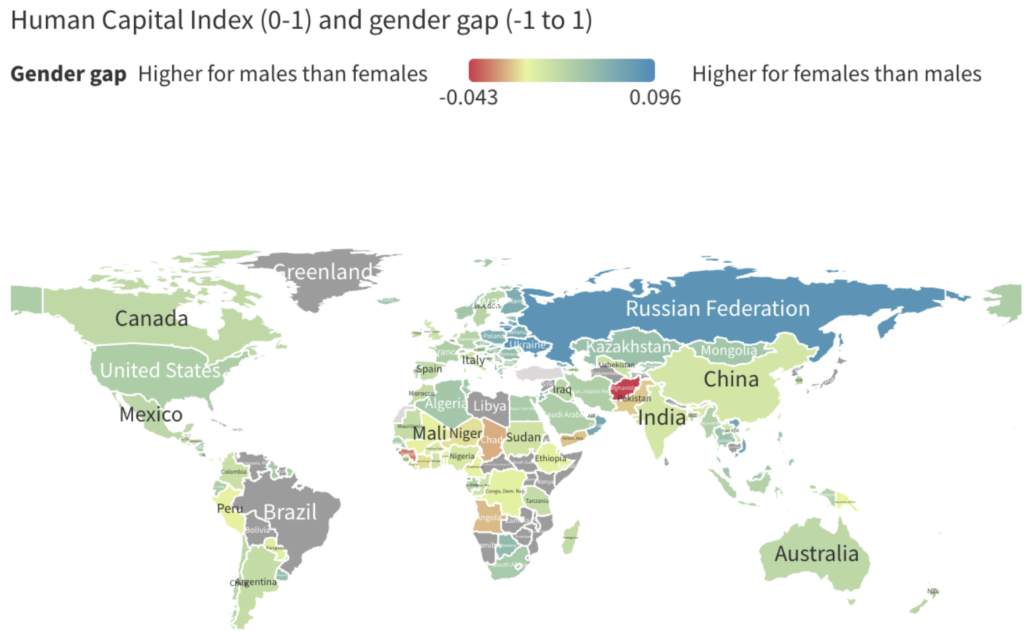

As we read the various data — like these five charts on gender (in)equality around the world from the World Bank — the first thing that stood out to us is that girls’ education is an area where we have a lot to celebrate. Although there are stubborn pockets of education exclusion for girls (particularly in Africa, and particularly for girls in hard-to-reach areas or from poor families), “Girls’ human capital [a major component of which is expected years of schooling] is now equivalent to or higher than boys’ in 90 percent of countries with sex-disaggregated” data.

The latest findings from ASER in India show that between 2017 and 2023, the gap between male and female school enrollment for 14-18-year-olds has narrowed from 4.1 percentage points to just 0.2 percentage points. Females in this age group are more likely to aspire to higher levels of education than males. Research on Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence (GAGE) in Ethiopia similarly shows that girls’ educational aspirations are high and enrollment in school is strong. Usawa Agenda’s recent report on foundational learning in Kenya finds that boys aged 4-15 are more likely to be out of school than girls. In short, there has been strong progress in girls’ education access, enrollment, learning outcomes, and even education aspirations.

The second thing that stood out to us from data published around International Women’s Day is that progress towards gender equality in other areas is less promising. Those same World Bank charts indicate that gender-based violence remains prevalent and women remain under-represented in leadership and the labor force. When women do have access to formal employment, recent evidence from Ethiopia suggests those jobs are likely to be politically disempowering. According to Equal Measures 2030’s SDG Gender Index, a third of countries are either making no progress towards gender equality or, worse yet, are backsliding.

In sum, despite traction on gender equity in education, other areas of gender equality remain less tractable and there are plenty of forces pushing us towards backtracking. Why? And what can we do about it — within the education system itself? This month’s Puggle focuses on the latest evidence answering these two questions.

Why are we seeing so much progress in girls’ education but not on other gender equality issues?

One hypothesis is that we have not measured the right things vis-à-vis gender and education. In their CIES panel “Protesting the status quo in Girls Education,” panelists argued that “we, as a field, continue to put more attention on enrollment, attainment, and a limited set of knowledge indicators, while not fully supporting work that has the potential to challenge assumptions, to rework inequitable socioeconomic and political structures, and to build an educational experience that is more fully one of quality for girls.” We are counting things that we can easily measure quantitatively (enrollment, attainment, skill development), which leaves out many things that matter when it comes to gender equality — like the gender-discriminatory norms children and youth face, including in school.

If we were measuring more of the right things, we would find that despite girls’ growing achievements in education, education is not equipping them with the skills, abilities, and agency to achieve equality in other realms. In India, ASER’s 2023 findings show that boys outperform girls on every assessment task besides basic reading. Moreover, girls were 4.5 percentage points more likely to refuse even to attempt to answer a question than boys were. Many of the assessment tasks asked youth to apply their skills to real-world problems. For example, they were asked to use Google Maps to determine how long it would take to reach the district bus stand. Only 16% of females could do this, compared to 36% of males.

“Girls are staying in school longer, but this does not imply that they are gaining the knowledge, skills, or confidence needed to successfully negotiate their lives as adults…The expectation that girls should conform to social and family norms and refrain from independent action clearly structures the lives and thoughts of many of them. How then can young women develop curiosity, critical thinking, and the courage to take risks?”

Finally, as alluded to in the quote above, even if education did a better job of equipping girls with ability and agency, social norms would continue to confine their choices outside of school. ASER finds that 20 percentage points more girls do domestic chores every day than their male peers, and very few girls push back on that expectation. In a podcast episode on low female labor force participation in India, Alice Evans interviews Suhani Jalota and Lisa Ho and posits that men make most decisions and their honor rests on women not working. Unless that changes, women can have all the aspirations and role models in the world, and it will still be difficult for them to work outside the home. Education cannot solve gender equality in isolation of other structural, policy, and normative barriers. But it could do more.

What can we do to push for greater gender equality through the education system?

First, we can push for education systems to address the root causes of gender inequality — including through explicit instruction on gender and power that aims to shift gender norms. We heard a lot about the possibilities of this type of work—otherwise known as gender transformative education—at CIES.

For example, we organized a CIES panel on Promising Approaches in Gender Transformative Education, highlighting exactly that. Raising Voices work in Uganda has led to dramatic declines in school-based violence and shifts towards embracing “gender fairness.” UNGEI’s work to end gender stereotypes in schools in Niger, India, and Bangladesh has increased students’ ability to recognize and challenge gender stereotypes. Equimundo has worked with youth in Washington, DC to deconstruct gender roles, leading to more gender-equitable attitudes and better reproductive health outcomes. And Breakthrough has successfully shifted not only gender attitudes and beliefs but also the behaviors of boys in India. You can see their presentations here.

Other panelists highlighted the importance of starting work to shift gender norms in children’s earliest years. We don’t often talk about gender inequality with young children because girls and boys generally participate in and learn at similar levels in preschool. However, gender is critical in the early years because that is when gender socialization happens. Starting from birth, young children are learning about gender and the stereotypes and biases associated with this through implicit and explicit cues from their environment (caregivers, educators, broader community). By the time they reach primary school, they are imitating gender roles and behaviors.

In Catalyzing Gender Transformative Approaches to Early Childhood Development in Africa, colleagues from BRAC, Children in the Crossfire (CiC), Lively Minds, and Ubongo shared best practices and lessons learned from early childhood education programs using a gender transformative approach in East and West Africa. You can view their slides here. Similarly, a panel on Achieving equality in and through education highlighted the importance of shaping gender norms more expansively when children are young, the ways in which girls face educational disadvantages in preschool even when they are not visible on the face of things, and the importance of eliminating the caretaking constraints that hold women back.

Second, instead of explicitly challenging gender norms in schools, we can teach students a wider range of skills to better equip them to navigate through education and life. A hot-off-the-press Life Skills Policy Brief from J-PAL Africa reviews 16 RCTs on life skills programs, finding that they consistently improve outcomes related to girls’ agency (“power within”) and education. The impact comes through at least four behavioral mechanisms: (1) Improving girls’ “power within” (confidence, aspirations, and gender attitudes), allowing them to envision different alternatives for their lives; (2) Providing girls with additional information that changes the cost-benefit calculations of investing in human capital development; (3) Giving girls tools to negotiate for what they want; and (4) Helping girls build stronger social networks to support their decision-making process. J-PAL Africa has also partnered with the Girls Education Challenge on a life skills program design guide that offers practical considerations for designing and implementing life skills programs.

Also, hot-off-the-press is a new book from the Assessment of Life Skills and Values (ALiVE) consortium on The Contextualisation of 21st Century Skills Assessment in East Africa. In this (open access!) book, you can read about how organizations across Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania came together to create contextually appropriate measures of life skills and values in the region. You’ll find out more about the skills they chose to measure — problem-solving, self-awareness, respect, and collaboration — how they defined the constructs, developed assessment tools, pushed for policy change, and generated regional capacity in the process.

Third, we can push back against women’s underrepresentation in governance by embracing female leadership in education. Usawa Agenda found that although 60% of Kenyan teachers are women, it is men who manage the schools — only 30% of school heads are female, and only 10% of chairpersons of Boards of Management are women. This is indicative of a broader trend unearthed in Global School Leader’s recent Review of Research on Gender in School Leadership. “Female school leaders account for only 26% of the overall proportion of school leaders in low-income countries, compared to 53% in high-income countries.” Even so, correlational evidence suggests that students attending schools with female leaders perform better. Those leaders are more likely to adopt good practices like creating strong learning environments, promoting teacher attendance, and engaging parents in conversations about their children. We can work to support more women school leaders through mentoring, networking, and equitable frameworks for recruitment, promotion, and professional development.

Lastly, we can support movement building for gender equality. Equal Measures 2030 highlights evidence of the role of strong feminist movements in driving towards gender equality. And the team at Purposeful outlines the importance of resourcing girls and women who are organizing with each other and “determining their own roadmaps to liberation.”

What else did we read with interest this month…

- Global School Leaders published a toolkit on How to Scale with the Government, offering 30 tools for influencing government policy design and implementation.

- The first edition of a new biennial Global Report on Teachers underscores an urgent global teacher shortage — we are expected to be short of 44 million primary and secondary education teachers by 2030.

- Experimental Evidence on Four Policies to Increase Learning at Scale finds that efforts to support remedial/targeted instruction in Ghana “increased girls’ test scores by about 0.1 SDs more than boys’ scores.”

- The Population Council published girls’ education profiles of seven East and Southern African countries: Kenya, Ethiopia, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia.

- Research from Niger finds that middle school scholarships and tutoring increased education engagement and shielded girls from child marriage.

- The Central Square Foundation released a report Examining Early Childhood Education in India.

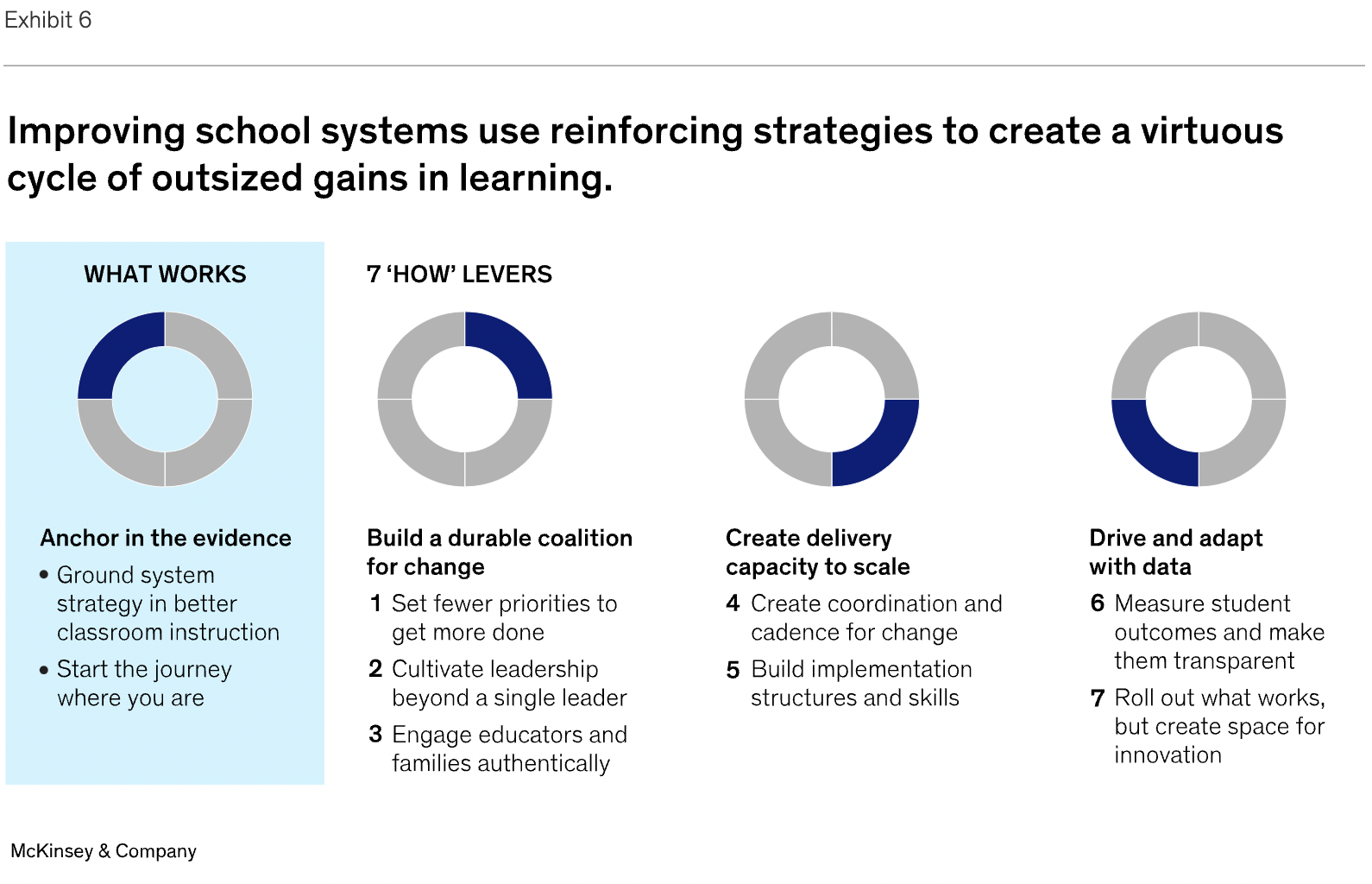

- McKinsey looks at seven levels for How all of the world’s school systems can improve learning at scale.