Over the course of May one of Echidna Giving’s advisors, Ruth Levine, wrote a series of six reflections as she approached the end of her eight-year tenure at the Hewlett Foundation. In Strength in numbers: Taking a field-level view and All happy grantees are alike: They focus on ideas, interactions, and important details, Ruth peels back the curtains on how (some) foundations think about their work. It’s not easy to find transparent reflections on the inner workings of philanthropy, so we thought you might find these of interest. The ideas certainly resonated with the way the Echidna Giving team thinks about much of its work.

When it comes to inner workings of other development donors, Oxfam wants to see more work on Feminist Aid, and put out a call for G7 leaders to beat inequality. The report argues that “A feminist approach to aid has the power to transform societies…It follows a rights-based, transformative approach to strengthen women’s and girls’ capacity to mobilize their own power, and that of other stakeholders, to shape their own futures.” It goes on to ask G7 leaders to commit to four approaches at their August summit: (1) “Make gender-based analysis mandatory across all aid strategies” (a mainstreaming approach); (2) Invest in stand-alone programming that addresses the structural causes of gender inequality” (a specific focus on advancing gender equality); (3) “Invest in women’s rights and feminist organizations;” and (4) “Ensure feminist implementation that fosters women’s agency.”

Canada recently took action on the third with the recent launch of a $300 million Equality Fund that will fund women’s rights organizations in developing countries.

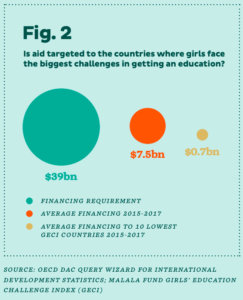

Given the role education plays in promoting economic and gender equality for this generation and the next, it can be key in feminist aid policy. The Malala Fund argues that G20 and G7 leaders could be doing more to address the education crisis. New analysis in Financing at Full Force shows that “donor funding remains short of the financing required to reach global goals, does not reach countries where girls’ education challenges are highest and does not adequately integrate a gender focus.” For example, the 10 countries with the greatest gaps in girls’ education get just 10% of global aid to education. The paper asks the G20 and G7 to provide additional funding to poorer countries in support of national education sector plans that help ensure all girls learn and earn.

For an insightful read on what it would take for politicians to take on these asks, Barbara Bruns offers an analysis of The Politics of Education in Developing Countries: From Schooling to Learning. In this book, Hickey and Hossain theorize that places where political “power is strongly consolidated, can be good for education reform because leaders have the political space to focus on longer-term development outcomes.”

When it comes to one specific policy recommendation, Are Female Teachers Better for Girls’ Education? “The fact that several studies show positive impacts of female teachers suggest that this area merits further exploration, especially as we follow the impacts across all aspects of girls’ well-being.”