A new report from the Center for Global Development looks at Girls’ Education and Women’s Empowerment: How to Get More out of the World’s Most Promising Investment. Building on the many existing reports and studies on girls’ education, the report focuses on what education systems and broader societies can do differently to make sure education translates more directly to better life outcomes for girls.

The report provides a good summary of many ideas that will be familiar to avid Puggle readers — e.g. that despite progress in educational opportunities for girls, in many places they still lag behind boys. That girls’ education delivers many benefits. And that despite significant evidence showing what it takes to get girls in school and learning, many girls (especially from poor households in rural areas) are missing out on the benefits of education.

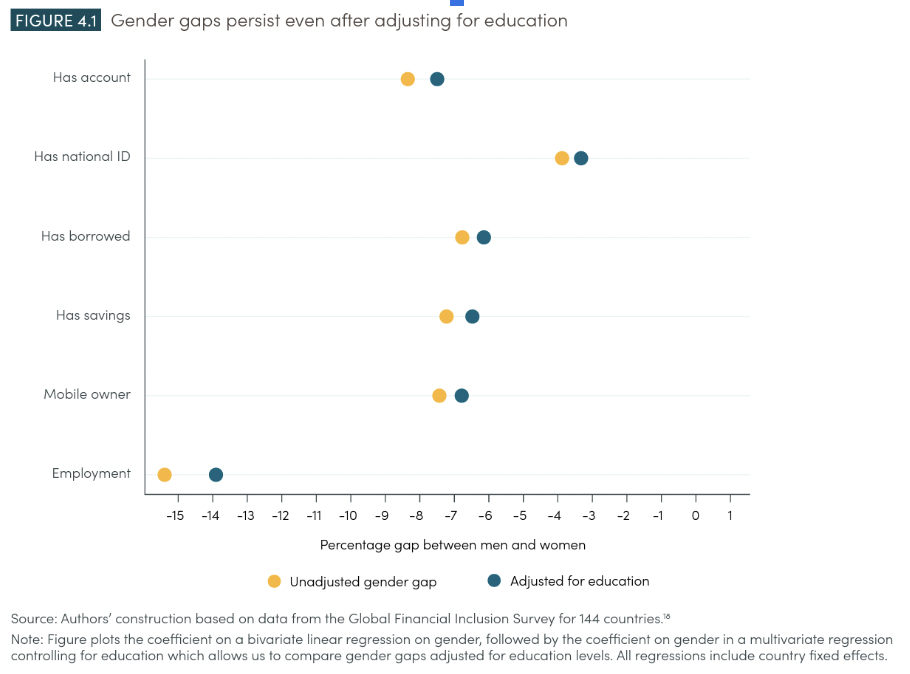

Then the report goes a step further by unpacking the reality that more equal education outcomes for girls does not necessarily translate into greater gender equality later in life. For girls’ education to be even more transformational, we should be looking at how education systems can contribute to gender equality beyond school — e.g. by shifting the biases that are often communicated through textbooks (go Kerala and its gender audit of school textbooks!), gender representation among teachers, curriculum, and exams.

We should also look at what policies outside of the education sector might also be needed through reforms like outlawing gender discrimination in access to credit and wages, putting in place quotas in political leadership, and subsidizing childcare. “Because the benefits of girls’ education are dependent on more than just getting girls through school…The system-wide gender equity agenda is all part of any effective agenda for girls’ education.”

If you read only this summary (or CGD’s blog and/or this twitter thread) you’ll be missing out on a lot of other rich information and details in the full report. Like an original analysis of donor project documents to determine what the hype and attention around girls’ education has translated into in terms of donor funding — hint: even when project documents talk about girls as a priority group, the majority of the time they do not include specific interventions targeting girls.

Education can do a lot more for gender equality, but it can’t do it all. What about climate change — can education also do a lot more about that? This question was top of mind in May when India and Pakistan continued to be crushed by record-breaking heat waves. Christina Kwauk shares 4 alarming findings about education across countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions, and argues that “Education stakeholders must begin to act as climate stakeholders. And education actions must be integrated as climate actions.”

Separately, this month the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) published Mind the Gap 2: Seeking Safe and Sustainable Solutions for Girls’ Education in Crises. The report focuses on three themes: (1) Distance learning for girls; (2) Gender-based violence (GBV); and (3) Girls’ education and climate change. The report argues that “Girls’ education can play an important role in climate change mitigation and resilience…through increasing climate resilience and adaptive capacity, empowering women and girls to participate in decision-making forums to address the impacts of climate change, and through technical and vocational education and training (TVET) and green skills.”

The type of care and education that girls receive in their earliest years contribute significantly to their later success in education.

A recent paper from Kenya underscores this fact — using longitudinal data from Kenya the authors find that the level of skills students had in math and literacy when they entered school (at roughly 6 years old) were predictive of their reading and math achievement at the end of Grade 2.

A new modeling study published in the Lancet looks at ten indicators of nurturing care for children ages 3-6 across 137 low and middle income countries (LMICs). The authors find that roughly ¾ of that age group in LMICs did not receive adequate nurturing care (responsive caregiving, early learning, safety and security, nutrition, and health). Pre-school-aged children are especially missing out when it comes to support for early learning, responsive caregiving, and safety and security (living without physical punishment).

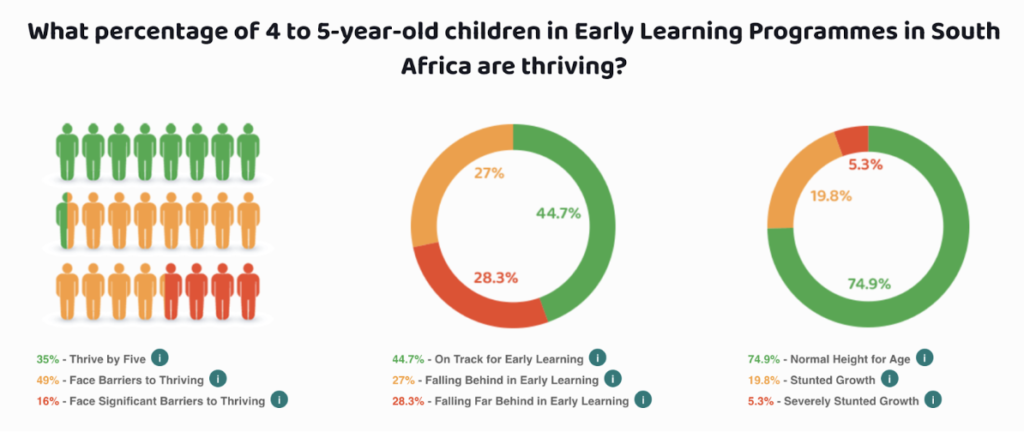

In South Africa, a collaborative effort across the private, public, and non-profit sectors pulled together a new Thrive By Five Index. Their nationally representative survey of preschool children found that just 44.7% of children are on track for early learning.

Fortunately, there’s a new resource of “evidence-based, cost-effective, and actionable strategies for delivering quality early childhood education (ECE) at scale in low- and middle-income countries to support policymakers and practitioners in closing these gaps. The World Bank recently published Quality Early Learning : Nurturing Children’s Potential, synthesizing evidence across disciplines “on how young children learn most effectively and how ECE programs can foster children’s natural ability and motivation to learn.”

We hope you can dig into some of the rich resources above to inform your own work and thinking.

And if you’re an African organization with an annual expense budget under $500,000USD/year, consider applying for the David Weekly Family Foundation Acceleration Portfolio by the end of this month!