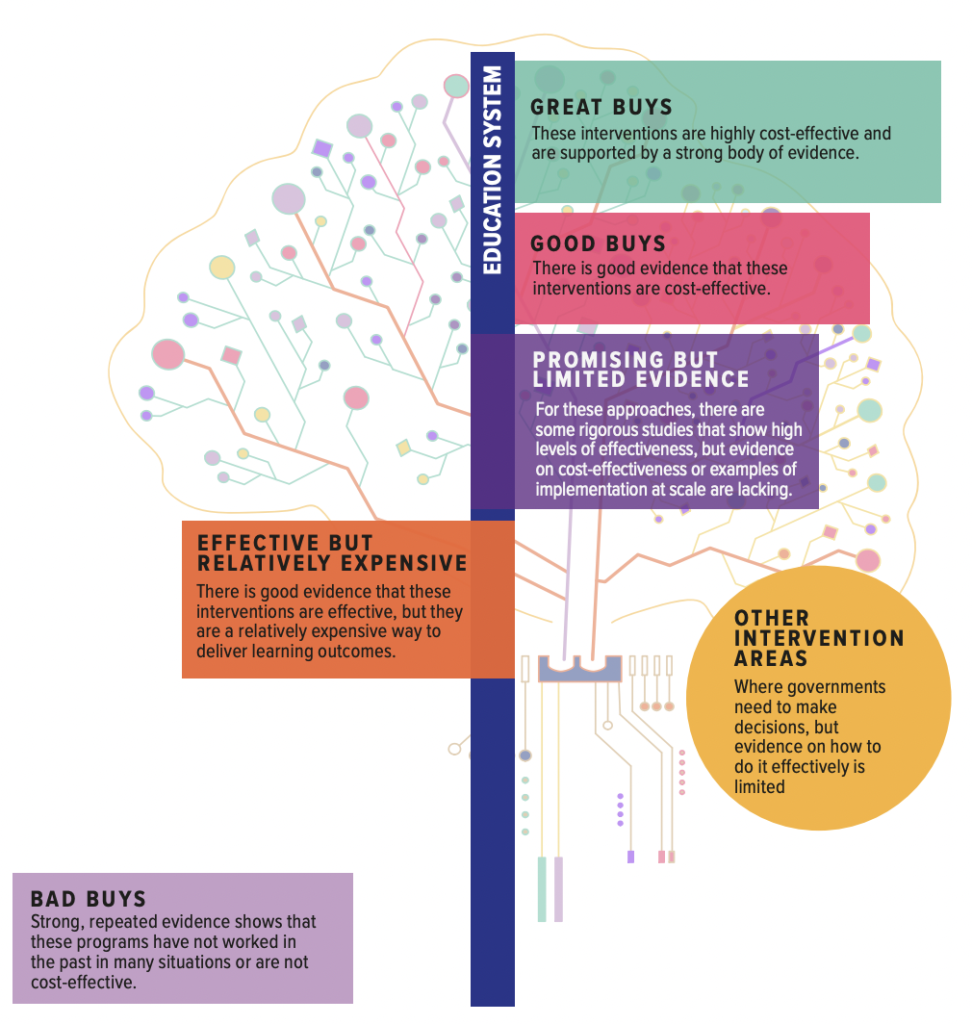

In May, the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel released a new report on Cost-effective approaches to improve global learning, an update to their first report in 2020. “Over 400 additional high-quality evaluation studies” were reviewed for the latest report, including additional intervention categories: “health and nutrition interventions delivered through schools that could impact education outcomes, and the literature on socio-emotional interventions.” Unlike the first review, this one looked at credible proxies for learning outcomes, which means that more studies on early childhood interventions were included. And the panel “placed even greater emphasis on scalability, giving higher weight to interventions that had been studied or implemented at larger scale and had been successfully adopted within government systems.”

In the final analysis, a couple of interventions moved from “good buys” to “great buys”: supporting teachers with structured pedagogy and targeting teaching instruction by learning level.

One intervention moved from a “promising but low evidence” category up to the “good buy” category: providing parent-directed early childhood stimulation programs to children ages 0 to 36 months.

Two interventions moved from a list of things governments need to make decisions about but don’t have much evidence around to the “promising but limited evidence” list: safeguarding students from violence and targeting interventions towards girls.

And a slew of new interventions were added to the list, almost all to the “promising but limited evidence” category: teaching socio-emotional and life skills, augmenting teaching teams with community-hired staff, providing mass school-based treatment of specific health conditions, leveraging mobile phones to support learning, and administering school-based mass deworming where worm-load is high (this last one is the only new item to make the “good buys” list).

Also of note: transferring cash (as a tool for improving learning) was moved from the “bad buys” list and added to a new category: “effective but relatively expensive.” One new item—feeding in primary schools—also made the list in this category.

It seems like a good reframe for these investments, particularly in light of the arguments in this piece about how economists’ focus on cost-effectiveness analysis led them to argue against prioritizing funding for AIDS treatments in Africa. In retrospect, the piece argues, funding treatment was a success because “Contrary to the tenets of the simple, static, comparative cost-effectiveness analysis, cost curves can sometimes be bent, some interventions scale more easily than others, and real-world evidence of feasibility and efficacy can sometimes render budget constraints extremely malleable.”

It is good to see the added range of interventions covered in the report, limitations of methodology notwithstanding. It will also be interesting to see what evidence gets added to the mix over time, particularly in areas that seem to be gaining traction and more evaluation dollars as well. For example, the most recent learning brief from the Girls’ Education Challenge fund finds across its projects that increases in social and emotional learning scores, higher levels of self-confidence, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and agency all correlate with improved learning outcomes.

If you’re looking to source information or ideas in the foundational learning space, check out the Evidence Map just launched by the PAL Network. It highlights 115 interventions and innovations that improve children’s basic reading and math outcomes. Don’t miss this treasure trove!

We were also interested in this case study on how Mississippi — the state in the U.S. with the highest rates of child poverty and hunger — has dramatically improved children’s reading outcomes.

“You cannot use poverty as an excuse. That’s the most important lesson,” Deming added. “It’s so important, I want to shout it from the mountaintop.” What Mississippi teaches, he said, is that “we shouldn’t be giving up on children.”

It’s interesting to look at the ingredients of success called out in the article: (1) increasing reliance on phonics and a broader approach to literacy called the science of reading; (2) a major push for teacher development through ongoing, onsite coaching; (3) significant investments in high-quality, full-day pre-primary programs, targeting low-income areas, delivered by well-paid teachers; (4) accountability for every child reading by the end of third grade — in the form of a “gating” reading test at the end of third grade; and (5) An iterative approach: “Mississippi kept testing and tweaking its model, following the evidence where it led.”

Despite the evidence in favor of pre-primary education (including its contribution to success in MIssissippi), a new report by Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre finds that aid to pre-primary decreased by 9.4%, compared to 6.9% decrease in overall education aid during COVID (2020-2021). And, distressingly, a new study from the Population Council shows that 2-4 year old girls are 19% less likely to attend higher quality private preschools than their brothers in India. These are the types of gender dynamics that often get lost in bigger picture reports, so we are grateful for this deeper analysis.