The end of 2020 is (finally) in sight. So, where do things stand with respect to education? In this Puggle we provide some big picture updates on education systems and funding, we offer a few snapshots of the impact of the pandemic on education in sub-Saharan Africa and India, and we close with some research and sources that might be helpful to inform how we move forward.

BIG PICTURE

Perhaps the biggest news in November — for education and everything else — was that several drug companies announced that their vaccines are highly effective in preventing COVID-19. That said, the prospect of a vaccine brings more clear and present benefits to some countries than others. In the meantime, in most countries, school systems have at least partially reopened. As of the end of November, UNESCO data showed that only 325 million learners were out of school (18.6% of the enrolled population), down from a peak of nearly 1.5 billion learners in early April.

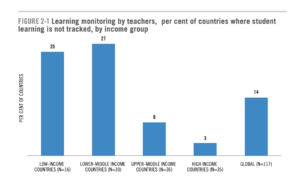

This positive trend notwithstanding, effects of the pandemic on schools have been far from even across countries. In a survey of ministries of education on national responses to COVID-19, UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank found that high-income countries were more likely to have reopened schools and to have provided distance learning in meaningful ways. As a result, in low- and lower-middle-income countries students have lost more instructional days. Teachers have been much less likely to monitor their students’ learning, and teachers and parents much less likely to receive support. Furthermore, more than a third of low- and lower-middle-income countries have “either already experienced or anticipate decreases to their country’s education budget for the current or next fiscal year.”

Recent research by the OECD Centre on Philanthropy raises similar concerns that donor funding for education could face a serious decline in the coming years. The report underscores how evidence-based decisions will be ever-more critical as resources become more scarce. It also describes the particular risks to girls’ education, arguing that not only do girls stand to lose disproportionately in the pandemic, but also that “development aid and private philanthropy show education has been losing ground as a critical entry point to support gender equality.” Of particular concern is the UK government’s foreign aid cuts put girls’ education at risk.

IMPACT IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA & INDIA

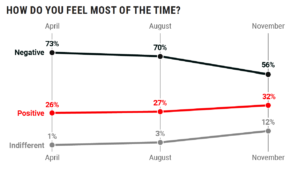

UNICEF calls COVID-19 a catastrophe for children in sub-Saharan Africa. The region is suffering its first economic recession and over half of children are dealing with food insecurity as a result. The World Bank estimates that in 77 percent of people in Ethiopia, Malawi, Nigeria, and Uganda are in households that have lost income due to the pandemic and 20 to 25 percent of the households don’t have enough food. Before the pandemic, 96 percent of students had contact with their teachers. Now, only 17 percent do. A recent COVID-19 Barometer from Shujaaz in Kenya shows glimmers of improvement — compared to April, young people are earning more and feeling better, though they still aren’t optimistic.

Meanwhile, in India, the Center for Budget and Policy Studies surveyed 3,000 households across five states in India and found that only 50 percent of boys and girls in households facing food shortages thought they would be able to go back to school when they reopen. While out of school, most girls are not able to effectively participate in learning. A full 71% of girls were employed in care work, compared to 38% of their male peers. Even when they had a phone at home, only 26% of girls could access it whenever they wanted to, relative to 37% of boys.

RESOURCES FOR MOVING FORWARD

For some good ideas about how we might help students recover from the scary trends above, read these reflections from seven years of research in J-PAL’s Post-Primary Education Initiative. One of the themes out of 140 rigorous research projects over the last 7 years is around girls’ empowerment. “A growing body of evidence…indicates that soft and life skills training programs, often bundled with other components, can improve adolescent girls’ self-efficacy, confidence, and attitudes toward restrictive gender norms.” Girls who were able to participate in an empowerment program in Sierra Leone during the Ebola outbreak were more likely to re-enroll in school after the outbreak and had more educated and supportive partners 5 years later.

For a good “one-stop-shop” for evidence on how COVID-19 is affecting children, check out UNICEF’s new COVID-19 Research Library. For daily visual updates on the impact of COVID-19 on the world’s school systems, see Insight for Education’s roll-up of global infographics, here. Also check out the COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker, which monitors the policies governments have put in place to tackle the COVID-19 crisis with a focus on three gender-sensitive measures: violence against women, women’s economic security and unpaid care.

The road out of the pandemic will not be an easy one, and the data above makes clear that there will be many obstacles in the path of getting children back and schools and learning. But we take some comfort in the old adage that it’s always darker before the dawn. We’ll keep pushing for daylight and sharing what we’re seeing and learning along the way!