If you’re looking for some holiday cheer, I’m afraid you won’t find it in the November edition of the Puggle. But if you’re looking for some concrete data and evidence on which to plan for the year ahead, look no further. This month’s post highlights the latest research on the impact of COVID on girls’ education, unearthing a number of potential risks to urgently address.

First is the risk the students — especially girls — will not return to school or will return with steep learning deficits and mental health challenges.

A survey carried out by Save the Children in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Malawi, Nigeria, Somalia, and Uganda, shows that “18 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, up to 1 in 5 of the most vulnerable children have not returned. This is not typically because of fear of the virus itself, but a direct result of child labour, child marriage, financial hardship, relocation and other consequences of the pandemic – and girls are particularly at risk.” Uganda’s National Planning Authority projects that “over 30 percent out of the 15 million learners that were in schools before the COVID-19 pandemic hit Uganda are likely not to return to school.”

One of the reasons students might hesitate to come back to school is because of the learning they missed out on while schools were closed. Among adolescent girls in rural Bangladesh, a study by the Population Council revealed significant learning loss during COVID, with girls from the poorest households suffering much more significant learning loss than their wealthier counterparts. Girls shared their anxiety about going back to school given that they had not yet mastered the material, especially since they would be automatically promoted. Their ability to go back will also be hampered by the increased risk of child marriage.

Even where pupils have returned to school, both boys and girls have steep mental health and learning challenges to surmount. Global School Leaders’ survey (and summary) of 11,667 educators from 24 countries found that 87% of school leaders are very concerned about the mental health of their students and 55% are worried that students are being left behind in curriculum.

The latest Annual Status of Education Report looks at how children aged 5 to 16 in rural India have studied at home since the onset of the pandemic and the challenges that schools and households face as schools reopen. As of the end of September, Indian schools had been closed for over 73 weeks compared with a global average of 35 weeks of school closures. The survey of over 76,000 households finds that 95.4% of enrollable children are enrolled in India, but the highest proportion of unenrolled children are 5 year olds, who are missing out on crucial early childhood education during the period when their brains are developing most rapidly. For students who are back in school and attending, teachers are struggling to deal with an influx of students with large learning deficits. 65% of teachers facing challenges said children were not able to catch up to the current curriculum and yet 75% of teachers are teaching at grade-level. Given the steep drop in foundational learning ability in government school students as a result of COVID-19, children may not be able to learn or cope with their re-entry into a schooling system that has left them behind.

Second, although COVID learning loss is not necessarily steeper for girls than boys, research suggests it poses the most acute risk for girls.

As Michelle Kaffenberger, Kirsty Newman and Marla Spivack argue, this is for two reasons. First, because girls “often drop out of school because they realise they are learning too little for education to provide a secure future.” Prior work shows that girls are more likely to drop out than boys as a result of weak school performance, so the impact of COVID learning loss is likely to be especially severe for girls. We need to address it in order to pre-empt future dropouts.

The second reason to look carefully at learning loss if we care about girls’ education outcomes is because “the benefits of girls’ schooling for their later life outcomes…are much larger when girls learn while they are in school [not merely complete more years of education]. One recent RISE paper estimates that achieving literacy, just one aspect of learning, accounts for one-third to one-half of the benefit of education to some later life outcomes.”

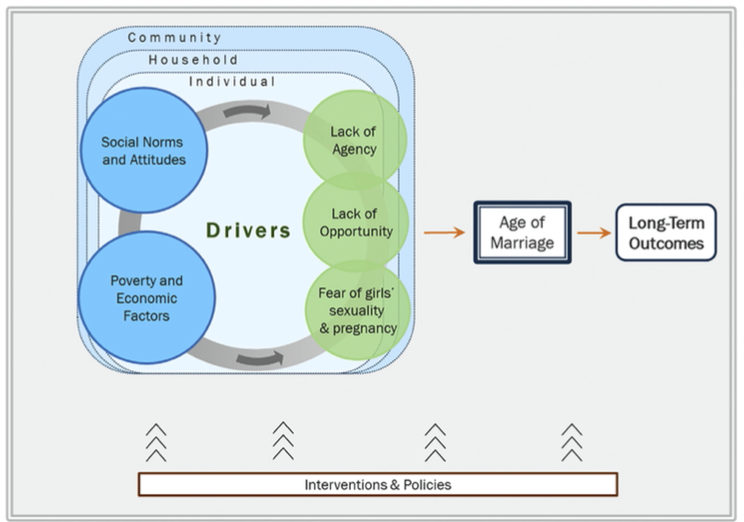

Third, the pandemic has exacerbated a number of the drivers of child marriage, which are synthesized in this new report. This underscores the risk that we’ll see an amplified negative feedback loop between the pandemic’s effect on child marriage and its effects on education.

Psaki et al.’s conceptual framework lays out five interrelated drivers which interact to induce child marriage for girls. Underlying all manifestations of child marriage are two core drivers: (1) social norms and attitudes and (2) poverty.

In terms of education, Misunas et al. (2021)’s comparative study of the drivers of child marriage in Burkina Faso and Tanzania found that girls with lower education attainment were significantly more likely to be child brides in both countries. Additionally, they found that having parents who support the idea of girls continuing education was a common and important preventative factor, speaking to the importance of education as a catalyst for change, both in terms of social norms and economic mobility.

Yukich et al. estimate there will be 7 to 10 million excess child marriages due to the pandemic if increased efforts are not taken to address COVID-specific drivers (e.g. death of a parent, interruption of education, pregnancy risk, household income shocks, and reduced access to child marriage prevention programs). Recent research also indicates that child marriage negatively impacts women’s economic outcomes mainly because these women attain less schooling and, consequently, acquire fewer skills. With immediate, concerted efforts to address the impacts of COVID on both schooling and age of marriage we can help create positive reinforcement where more schooling allows for less child marriage and less child marriage allows for more schooling.

As we think about the type of education girls’ need to attain in school, a new book offers critical perspectives on Life Skills Education for Youth.

The book looks to answer “Which life skills are important, for whom, and how can they be taught?”, with a significant emphasis on the gendered dimensions of life skills. In the concluding chapter, authored by yours truly, I highlight three broad themes from the book. “First, that teaching life skills helps marginalized adolescents in particular – but should not put the onus of overcoming marginalization squarely on their shoulders. Second, that consensus seems to be emerging that a cluster of social and emotional skills and cognitive abilities like critical thinking are particularly important for success. Third, that the way in which life skills are taught matters as much as which skills are taught.” Check out the book — and the conclusion — in their entirety for further insights on these themes and more.

And in case you missed it…

- The Brookings Echidna Global Scholars program hosted a Girls’ education research and policy symposium: Protecting rights and futures in times of crisis. Scholars shared insights and findings from their work on education in emergencies, technical and vocational agriculture education and training, the role of mentorship in young women’s transition to the labor force, and effective training and support for aspiring young women entrepreneurs.

- In a major promising reversal of policy, Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu allows teen mothers back in class.

- The Yidan Prize is looking for nominations of people shaping the future of education.

Be on the lookout for an annual wrap-up Puggle in the next week or two!