It’s been such a busy two months that you probably didn’t even realize a full two months passed since we posted our last Puggle, right? That’s certainly how we feel!

To catch up on lost ground, though, in this post we cover notable news from both October and November.

First, a few rapid fire updates around girls’ education:

- The four exceptional Echidna Global Scholars at the Brookings Institution presented on their research findings at a symposium on De/reconstructing education as a space for transformative belonging and agency. Don’t miss out on Halimatou Hima’s findings on forcibly displaced girls in the Sahel (forthcoming), Hina Saleem’s research looking into how a holistic education policy can help bridge the opportunity gap for girls in rural Pakistan, Bhawana Shrestha’s exploration of why promoting female teachers’ social-emotional learning matters, and Anthony Luvanda insights about girls and young women left out of digital technology education and careers in Kenya (forthcoming).

- The Obama Foundation launched the Get Her There campaign in support of girls’ education around the world with Melinda French Gates and Amal Clooney.

- UNGEI, UNESCO, and FCDO published a Baseline Report to monitor progress against the two girls’ education objectives that G7 heads of state set committed to in 2021: getting 40 million more girls in school; and getting 20 million more girls reading by the end of primary school.

- The African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of Children issued a landmark ruling denouncing Tanzania’s policy of expelling pregnant and married girls from school. It requires Tanzania not only to readmit girls and provide support to compensate for lost years, but also to provide sexuality education for adolescent children. The regional quasi-judicial organ of the African Union is tasked with monitoring implementation of the African Charter on Child’s Rights and Welfare, so its findings have implications for all 49 countries that have ratified the charter.

More broadly, we have seen a big push to underscore the importance of foundational learning, including in the very earliest years.

At the triennial Association for the Development of Education in Africa Conference in Mauritius in October, there was a major emphasis on the need to strengthen African education systems — including by building robust data systems and nurturing local research and think tanks across the continent to generate evidence-based solutions for African problems by Africans — particularly to invest in improving foundational learning.

(Unfortunately, there was not much of a focus on gender either in the agenda for the conference nor in the papers presented.)

The conference included the launch of a spotlight report on basic education completion and foundational learning in Africa, Born to Learn, developed by UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report in partnership with ADEA. Although all children are born to learn, “the report shows that children in Africa are at least five times less likely than children in the rest of the world to be prepared for the future.” One in five children are out of school and 1 in four will never complete primary education.

Many similar points are echoed in RISE’s recent policy paper, Focus to Flourish, which underscores the central challenge of cultivating foundational learning for all children.

The short powerpoint “explains the five actions to accelerate learning, drawing on the cumulative body of research” from RISE and elsewhere:

- Commit to universal, early foundational learning

- Measure learning regularly, reliably, and relevantly (Of note: UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics has launched a Learning Data Toolkit to help with this one)

- Align systems around learning commitments

- Support teaching

- Adapt what you adopt as you implement

While evidence on literacy programs is becoming more robust, evidence on how to support numeracy lags behind. The Center for Global Development published a new study looking at Numeracy at Scale: Introducing a New Study on Successful, Large-Scale Numeracy Interventions, which collates what we do know, and underscores the importance of more efforts in this area.

In addition to the measures above, this recent piece from The Atlantic argues that a “child’s ability to succeed in the classroom is strongly influenced by the level of support they receive at home.” It focuses in particular on the importance of supporting parents during the very critical first years of their children’s lives. Two recent events underscored the same.

First, the World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education culminated in the Tashkent Declaration which was adopted by representatives of 150 countries. The declaration includes guiding principles for “equitable and inclusive quality ECCE services for all.” Although there was push and pull around what went into the final declaration, champions for early childhood education noted how much progress has been made towards prioritizing ECCE in the last decade.

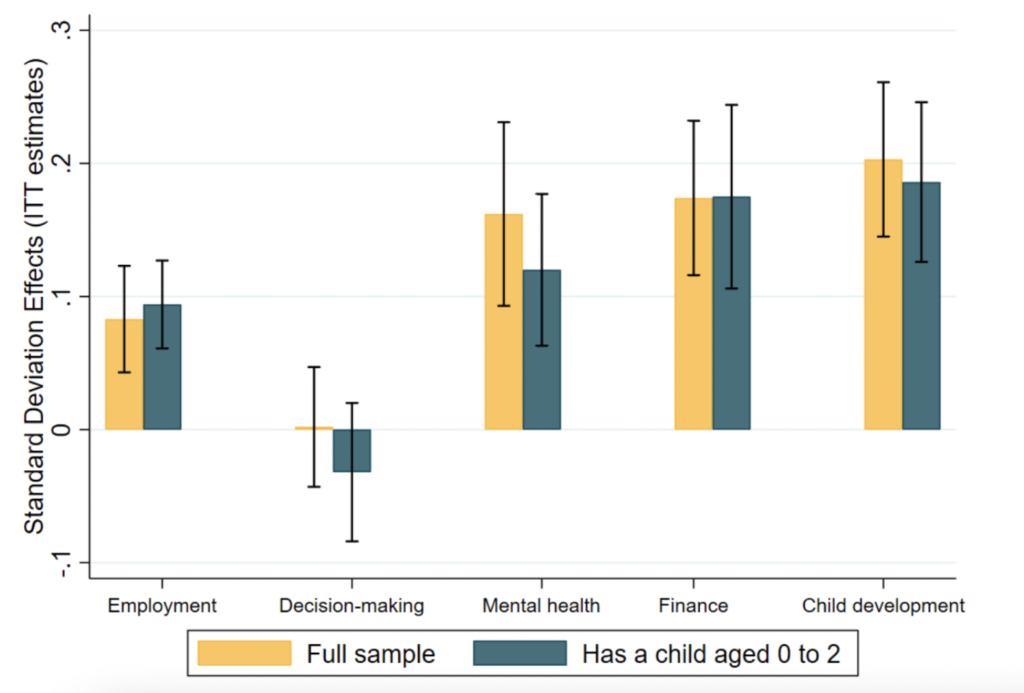

Second, the Center for Global Development’s Birdsall House Conference on Gender Equality examined how childcare could advance the needs of both women and their children. Kehinde Ajayi presented research from a public works program in Burkina Faso that introduced childcare as part of the model in half of the work sites. Their new paper looks at whether these community-based childcare centers improved early childhood development and increased women’s economic empowerment. The short answer, for both, was yes, and substantially so. “Children in sites with the new childcare centers had improved early childhood development scores, with a 0.2 standard deviation gain on average,” and that’s despite the childcare centers being closed for a third of the study period due to COVID-19.

Not only that, but the program paid for itself in returns to women’s wages. This aligns with wider research looking at the return-on-investment to childcare funding.The takeaway? Childcare presents opportunities for considerable returns for children, caretakers, and the broader economy.

Last, but not least, here are three things to add to your holiday reading (and listening) list:

| “When we Thrive our World thrives: Stories of Young People Growing Up with Adversity” authored by Connie K Chung with Vishal Talreja, founder of Dream a Dream. You’ll find compelling personal stories of 20 young people, examining what it means to grow up with adversity and thrive. | Human Capital and Gender Inequality in Middle-Income Countries, co-authored by Elizabeth King and Dileni Gunewardena. They estimate “returns to different levels of schooling as well as cognitive and socioemotional skills for women and men,” and examine how context mediates these relationships. The findings show that investments in girls’ schooling can pay lifelong dividends. | Educate Us!, a podcast about women’s and girls’ education in humanitarian crises. Among other episodes, the podcast examines Who Gets To Learn During A Pandemic, Gender Responsive Early Childhood Education, and Engaging Men and Boys in the Fight for Gender Equality. |