We took a one-month summer hiatus from The Puggle, but rest assured that this edition covers key news and research related to girls’ education from both August and September. In other words, we’ve got an especially meaty update for you this time around. Before we get into all of that, please take a moment to encourage stellar girls’ education leaders to apply for the Echidna Global Scholars Program at Brookings before 10/15!

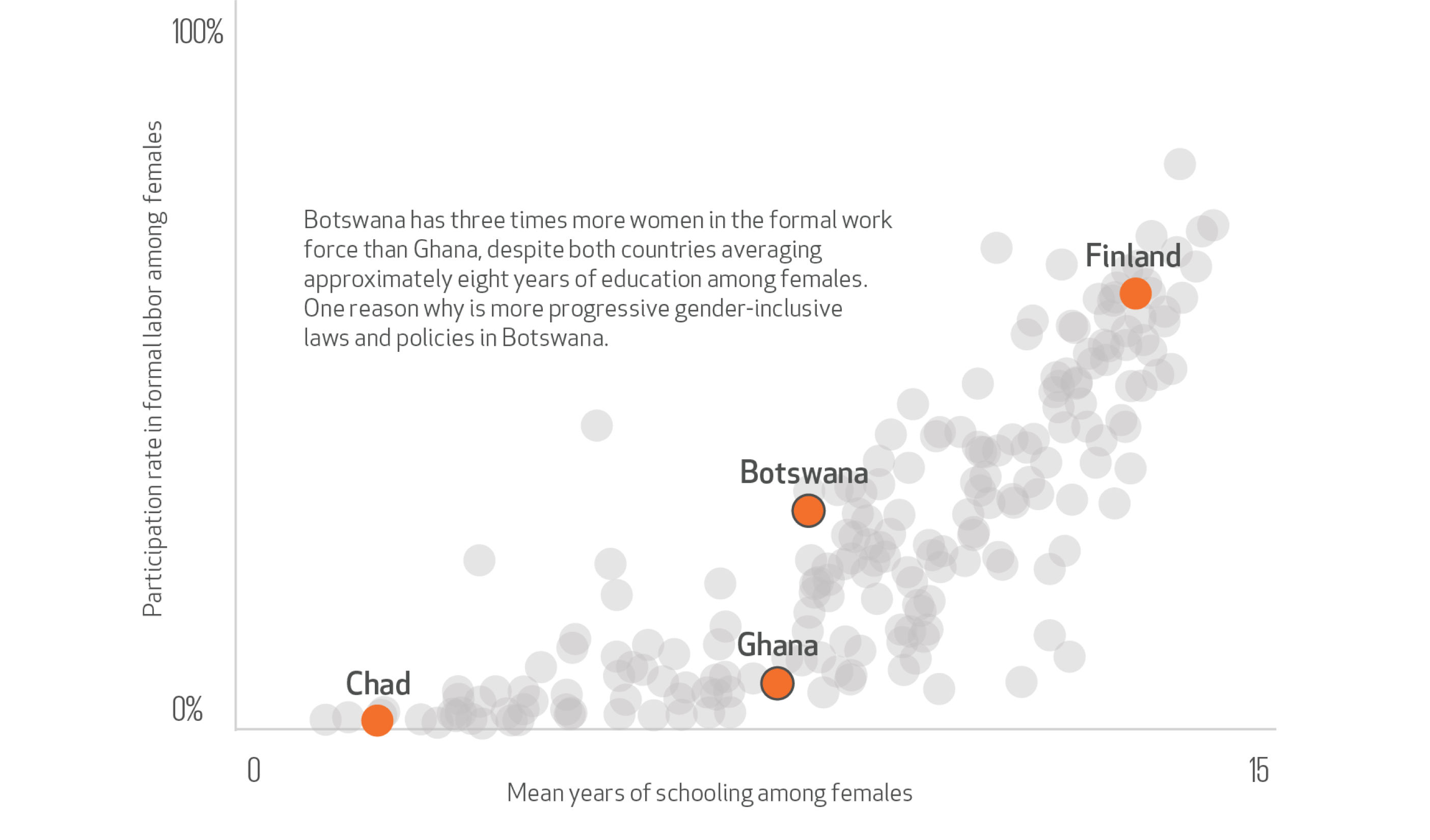

What it means to be a girl. According to the last of these 6 charts on gender gaps, it will take 136 years for women in Sub-Saharan Africa to reach parity with men. In their latest Goalkeepers report, Bill and Melinda Gates examine “how geography and gender stack the deck for (or against) you.” When it comes to education, “Across sub-Saharan Africa…girls average two fewer years of education than boys. [But] even when girls are well educated, they are much less likely to translate their years of schooling into a job in the formal work force.”

Why? In a recent paper, Seema Jayachandran outlines the role gender norms play in restricting women’s engagement in the workforce. She also explores how policies and programs can blunt the impact of social norms or even change the norms themselves. One set of approaches is to make it easier for women to balance work and family responsibilities, for example by providing childcare alternatives and interventions that make household chores less time consuming (check out recent evidence briefs from UNICEF on some of these policies).

Another is to directly target gender norms, including by using schools as the place to reshape adolescent gender attitudes. We supported a recent workshop at ICRW about Engaging Men and Boys to Promote Gender Equality Through Education that explored some of these interventions. Research and programming in this space is still relatively thin, as a recent review on addressing men, masculinities, and gender equality in sexual and reproductive health and rights found.

If you’re looking to measure the impact of your own programs and investments from a gender lens, check out the Gender Equality Toolbox recently launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The hard stuff and the soft stuff. We recently came across more evidence that “hard” skills alone are not enough—soft skills like self-regulation and critical thinking are important for everything from countering violent extremism to empowering at risk girls in Northern Nigeria. For a feast of perspectives on cultivating social and emotional skills, checking out this compilation of 42 articles on everything from how to contextualize social and emotional learning to how to bring it to life in the classroom and how to measure and monitor it.

Given we’re faced with “learning poverty,” as the World Bank puts it, around even basic skills, can systems realistically be expected to teach a wider range of social and emotional skills? Or should education systems prioritize “universal, early, conceptual and procedural mastery of basic skills,” as Michelle Kaffenberger argues? At a recent panel about innovative pedagogies to transform education, Denis Mizne, CEO of the Lemann Foundation, insightfully argued that good pedagogy might bridge the tension between improving basic skills and attending to the whole child, because good pedagogy can foster both. The Education Commission argues that better pedagogy could be supported by Transforming the Education Workforce.

What does the future hold? UNESCO has launched a Futures of Education initiative to catalyze “a global debate on how knowledge, education and learning need to be reimagined in a world of increasing complexity, uncertainty, and precarity.” Keep an eye out for the global consultation process that will be launching soon.

Does artificial intelligence have a role to play in the future of learning? If so, will it transform learning outcomes and help teachers foster students’ strengths? Or will it exacerbate standardized learning and leave students unprepared for a rapidly changing world? China’s grand experiment in AI education may give us some answers.

Show me the money. At the G7, Britain pledged £90m to a global fund that provides schooling for children in conflict zones. Around the UN General Assembly, Britain and the Netherlands announced their support to launch the International Finance Facility for Education—not without controversy about whether education should be financed by debt. Meanwhile, education pundits worry that the aid architecture for education is failing the world. And The State of Global Education Finance in Six Charts suggests that aid is but a small piece of the financing puzzle.