The Puggle: October 2023 edition

/ Aparajitha Suresh / The Puggle / November 20, 2023

In celebration of the first-ever International Day of Care and Support, our October Puggle focuses on why care matters for girls’ education work. We also celebrate Claudia Goldin’s landmark Nobel Economics Prize award — she is only the third woman to receive this award and the very first not to share it with male colleagues.

Typically, we measure the success of girls’ education in terms of improvements in educational achievement (school completion rates, learning outcomes) and often through declines in child marriage and child pregnancy rates – proven life-altering outcomes that can be measured prior to the age of 18, before we consider girls to be women. These are critical outcomes, to be sure.

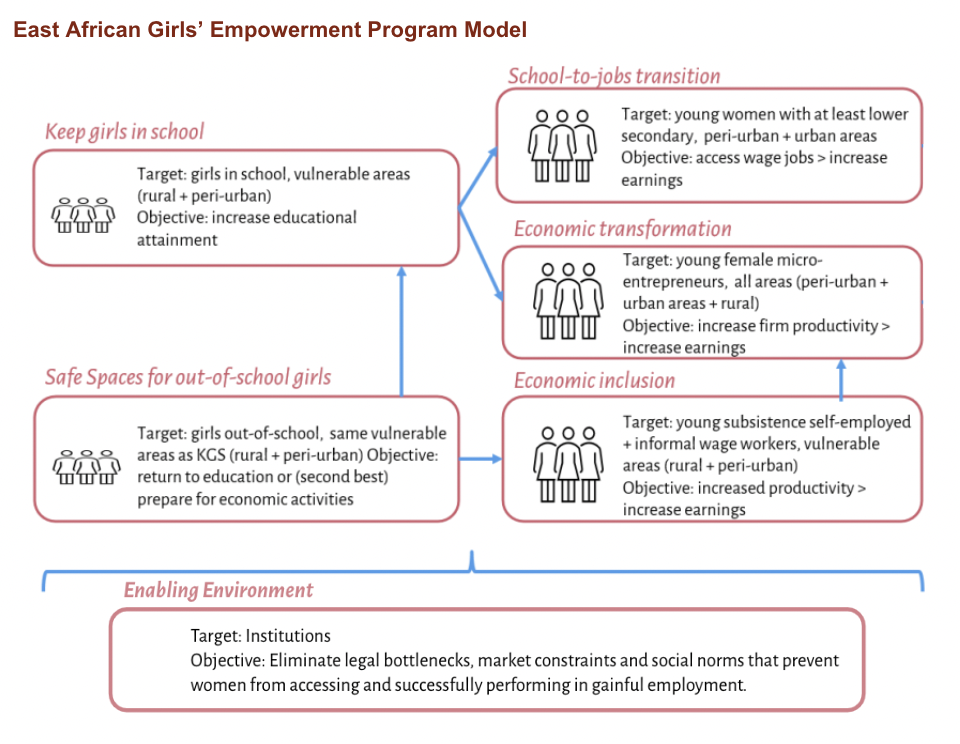

However, as Kehinde Ajayi notes, “the tide is changing,” with increased funding directed towards longer-term programming that prioritizes girls’ educational success and their later economic empowerment as adult women. For example, the World Bank’s newly announced East Africa Girls’ Empowerment and Resilience (EAGER) program considers the economic empowerment of girls and young women ages 10 – 35 as its end goal. It positions the material funding and effort allocated to ensuring girls’ completion of secondary school as a requisite for this.

Such programming aligns with the growing field-level understanding that “empowerment is not simply a question of equipping adolescent girls with opportunities and resources, but also of ensuring that girls are able to exercise control over them.”

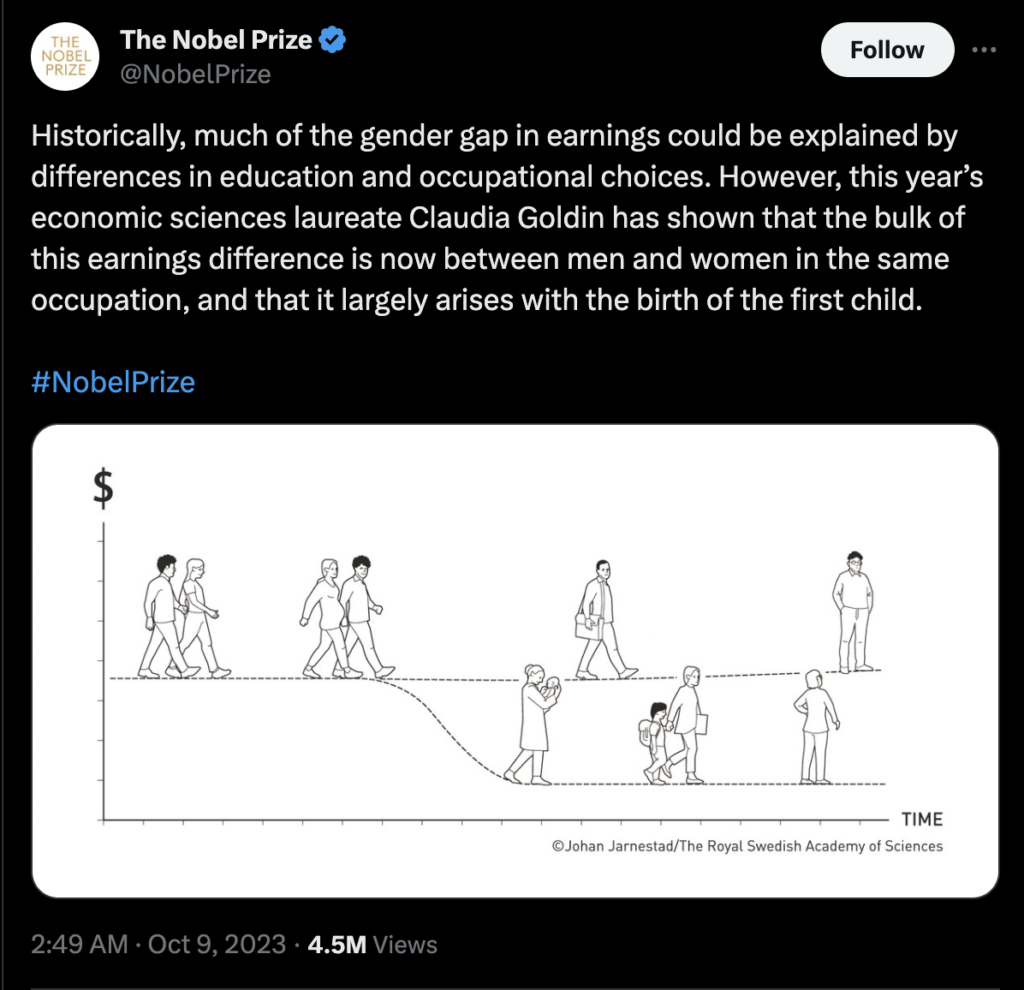

For girls to fully realize the benefits of their education as adult women, it is imperative that societies address entrenched gendered norms that place the responsibility of caregiving solely on females. Claudia Goldin’s Nobel Prize-winning research on the ‘motherhood penalty’ provides strong evidence for this:

In the U.S. context, Goldin shows that even with equal education, women are unable to participate equally in the labor force due to gendered care norms and practices. Following childbirth, women work ten fewer hours per week and make 40% less compared to fathers; meanwhile, men who become fathers start earning more.

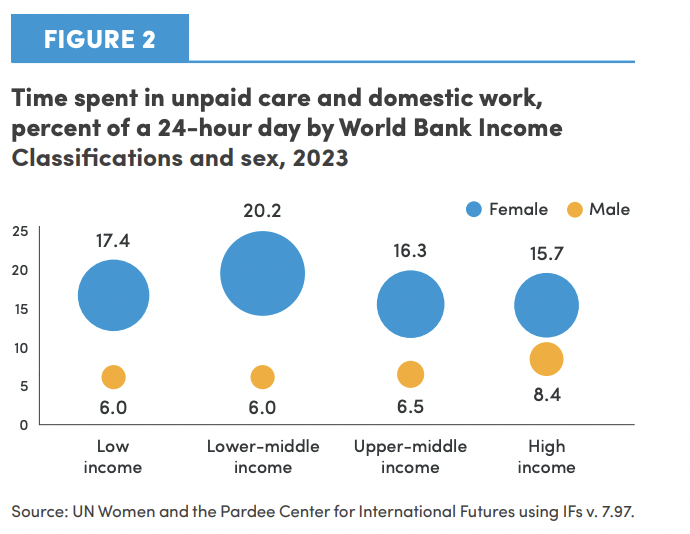

Similar research has yet to be conducted in low and middle-income country (LMIC) contexts where the ramifications of gendered care norms are even more pronounced — starting with the fact that the unpaid care burden placed on women and girls age 15+ is markedly higher in LMICs.

Presumably, Goldin’s finding that the bulk of the wage gap is between men and women engaged in similar occupations will not translate to the LMIC context, where (despite tremendous progress) girls still have yet to achieve parity in secondary school completion rates, let alone equal participation in the labor market. Rather, as a growing body of descriptive evidence indicates, gendered care norms may, in part, impact earning differentials due to time scarcity and increasing girls’ dropout rates.

In addition to immediately constraining women’s and girls’ equitable participation in gainful employment and education, gendered care practices have intergenerational impacts. Quantitative evidence from both higher income contexts and LMICs shows that when parents follow traditional gendered divisions of caregiving, their children are more likely to hold gendered beliefs as adults; but when parents distribute responsibilities such that fathers also contribute to childcare and housework, their children are more likely to hold egalitarian beliefs around gender as adults.

To ensure that the next generation of girls can grow into women who enjoy gender equity and that their children can carry this forward as the norm, it’s critical to reduce the female care burden and promote greater male engagement.

Advocacy for childcare as a state-provided public good promises structural change that would reduce the overall care burden on mothers and older sisters – opening doors for education and economic empowerment.

In isolation, publicly funded childcare cannot address the underlying inequitable norms that relegate most care work to females. But coupled with education to dismantle gendered stereotypes, we could begin to chip away at these constraints in a serious way.

In previous Puggles, we’ve highlighted the potential of Gender Transformative Education (GTE) to dismantle gendered stereotypes, norms, and practices that marginalize girls and women in broader society. The paragon of GTE in action is Breakthrough’s school-based work challenging regressive gender norms: Not only did the program cause sustained improvements in students’ gender progressiveness, but it also led to significant increases in the number of boys participating in household chore work – a noted strategy for raising boys who value & practice gender equity!